“A nation that destroys its soil destroys itself”

– February 1937, President, Franklin D. Roosevelt

In Pictures: The legacy’s of industrial ag advocates Earl Butz, and authors of the 1996 Freedom to Farm policy, Senator Pat Roberts, and Professor Barry Flinchbaugh.

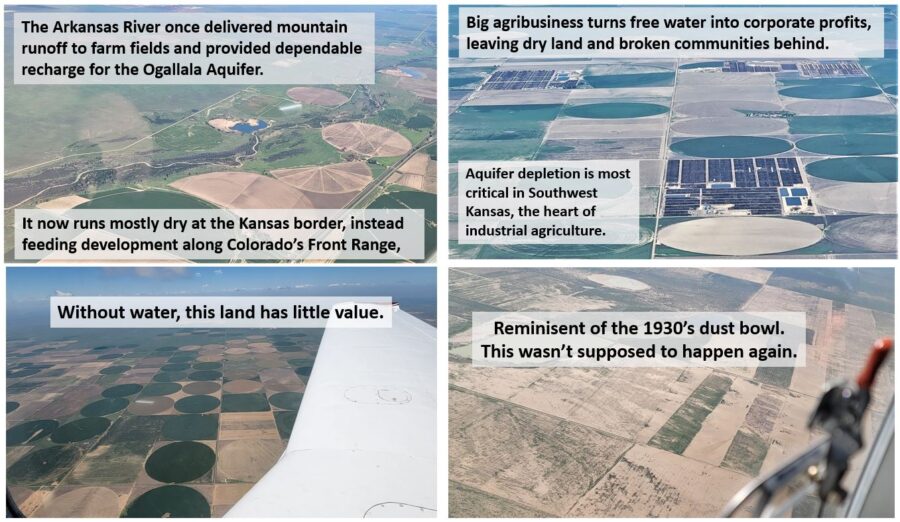

Current day on the eastern plains of Colorado and western Kansas

A reflection on the lasting legacy of 1970s USDA Secretary Earl Butz

Industrial agriculture lost one of its greatest champions last week: Earl “Rusty” Butz, secretary of the USDA under Nixon. Blustering, boisterous, and often vulgar, Butz lorded over the U.S. farm scene at a key period. He plunged a pitchfork into New Deal agricultural policies that sought to protect farmers from the big agribusiness companies whose […]

Tom Philpott

Published Feb 08, 2008

Industrial agriculture lost one of its greatest champions last week: Earl “Rusty” Butz, secretary of the USDA under Nixon.

Blustering, boisterous, and often vulgar, Butz lorded over the U.S. farm scene at a key period. He plunged a pitchfork into New Deal agricultural policies that sought to protect farmers from the big agribusiness companies whose interests he openly pushed.

He envisioned a hyper-efficient, centralized food system, one that could profitably and cheaply “feed the world” by manipulating (or “adding value to”) mountains of Midwestern corn and soy. Patron saint of the Fast Food Nation, Butz lived to see his dream realized. He died in his sleep, a quiet end for a man whose career shook the earth, causing untold acres to succumb to the plow. Yet his legacy still thrives, and will not likely die as gently as the man.

None of Your Agribusiness

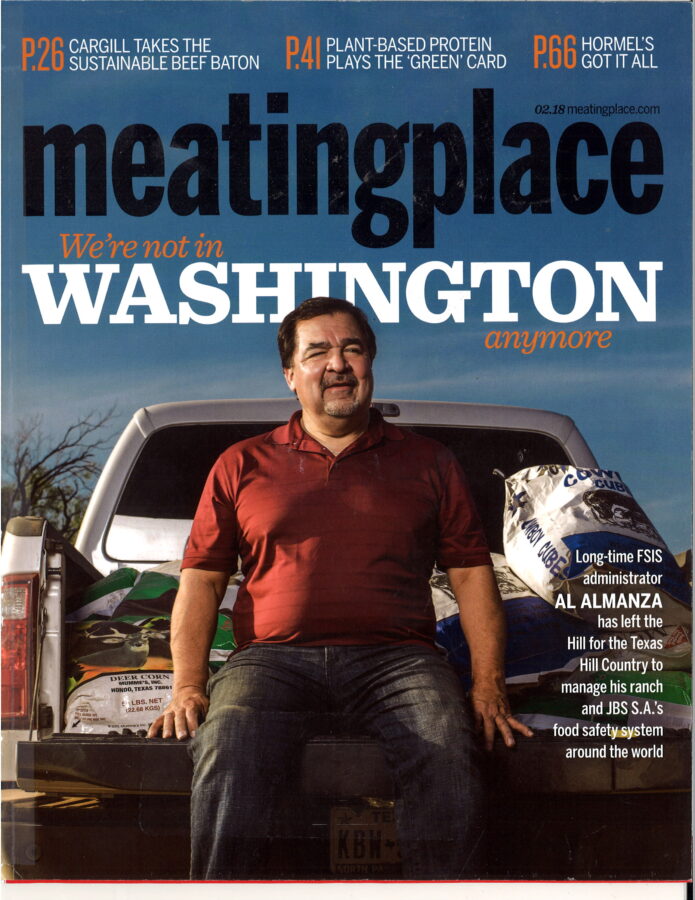

Nixon plucked Butz out of Purdue’s agriculture department and planted him in the USDA in 1971. At the time, Butz served as a board member for several agribiz firms, including Ralston Purina, then a sprawling food conglomerate. He rejected criticism that these ties might compromise his performance as USDA chief. (The habit of stuffing the USDA with industry cronies has proven hard to break.)

But Butz did forcefully equate the interests of agribusiness with the national interest.

All donations matched! Reader support helps sustain our work. Donate today to keep our climate news free.

And in 1971 as now, what agribusiness wanted was for farmers to plant lots and lots of corn and soy. In order to profitably mass-produce convenience fare for a growing middle class, the food industry needed unchecked access to cheap inputs.

But the ag policies of the day encouraged restraint. After the Great Depression — which featured the stunning confluence of huge grain surpluses, widespread hunger, and a tide of farm failures — the Roosevelt Administration put in place mechanisms to help farmers “manage supply.”

The program that Butz inherited worked like this: When farmers began to produce too much and prices began to fall, the government would pay farmers to leave some land fallow, with the goal of pushing prices up the following season. When prices threatened to go too high, the payments would end and the land would go back into cultivation.

The government would also buy excess grain from farmers and store it. In lean years — say, when drought struck — the government would release some of that stored grain, mitigating sudden price hikes. The overall goal was to stop prices from falling too low (hurting farmers) or jumping too high (squeezing consumers).

A side goal was to go easy on the land. The New Deal policymakers had seen how high-production agriculture could devastate land’s productivity. The “dust bowl” was a fresh memory.

For Butz and his agribusiness cronies, the program amounted to socialism — an intolerable check on farmers’ ability to plant and harvest as much as possible. By killing the “supply management” program, Butz would open a floodgate of cheap inputs from farms to food factories. Rather than use federal policy as a check on farm output, Butz saw it as a lever to maximize output.

To make the policy shift palatable in the Midwest, Butz needed to convince farmers that they weren’t risking a return to Depression-era conditions: vast overproduction, low prices, and foreclosures.

So he dangled the promise of foreign trade as a panacea. Don’t worry about overproduction, Butz told farmers on trips through the Midwest. Produce all you can, and we’ll the sell the surplus overseas!

Providing a grand example of how his vision might work, Butz engineered a massive grain sale to the Soviets in 1972. The move worked dramatically. The Soviets essentially bought up the U.S. grain reserve — just as a widespread drought hit the Midwest.

With the grain reserve hollowed out and the drought impeding the 1973 harvest, grain prices jumped and farmers scrambled to plant as much as they could to take advantage. Butz fanned their frenzy. “Plant fence row to fence row,” he exhorted from his bully pulpit. In other words, plow up and plant every bit of land you can get your tractor on. He brooked no dissent. “Get big or get out,” he routinely thundered.

Urged on by Butz and buoyed by high grain prices, millions of Midwestern farmers spent the 1970s taking on debt to buy more land, bigger and more complicated machines, new seed varieties, more fertilizers and pesticides, and generally producing as much as they possibly could.

Then, in the 1980s, the bubble burst. By that time, farms were cranking out much more than the market could bear, and prices fell accordingly. Meanwhile, interest rates had spiked, making all of those loans farmers had taken out in the ’70s into a paralyzing burden. Farm incomes plunged and tens of thousands of farms went under. Butz’s great policy change had given rise to the deepest rural crisis since the Depression.

Scorched Earth

Yet the food-production machine Butz created kept cranking. Surviving farms responded to low prices by planting more, hoping to make up on volume what they were losing on price. Failed farms got folded into larger operations at cut-rate prices. Throughout the Grain Belt, abandoned farmhouses were burned to the ground, cleared, and incorporated into ever-larger corn and soy fields. (For a blunt account of the farm-crisis period, see Osha Gray Davidson’s 1996 classic Broken Heartland: The Rise of America’s Rural Ghetto.)

While farmers scrambled to “get big or get out,” Butz’s beloved agribusiness giants cheered. Regaled with mountains of cut-rate corn, Archer Daniels Midland used its political muscle to rig up lucrative markets for high-fructose syrup and ethanol. In Iowa, bin-busting harvests gave rise to an explosion of massive concentrated-animal feedlot operations (CAFOs). An increasingly consolidated meat industry learned to transform cheap grain into cheap — but highly profitable — burgers, chops, and chicken nuggets.

It must have been satisfying for Butz to watch his vision come to life. But he endured personal humiliation along the way. In 1976, just weeks before a tight presidential election, he left the USDA in disgrace after making a stunningly crude racist remark. Five years later, he pled guilty to tax evasion and served a short stint in jail. But over the years — not unlike his political patron, Nixon — he returned to respectability. He died still holding an emeritus position at Purdue. (In a priceless scene in the excellent recent documentary King Corn, the narrators visit the aged Butz at his Purdue perch. I tried to interview him last fall for Grist’s Sow What? series; Purdue officials responded that he had grown too frail.)

And despite the rise of organic this and local that — a trend that annoyed Butz to no end — the old campaigner’s vision of maximum-production agriculture has become more entrenched then ever. He surely loved the way the biofuel boom has farmers worldwide scrambling to plant corn and soy and drench the earth with agrichemicals. Days after Butz died, the Wall Street Journal reported, “In the U.S., farmers … are razing old barns, ripping up sod and grassland, and uprooting fences — some in a routine attempt to improve land, others in an effort to make room for the grain boom.”

One Iowa land excavator told the Journal that farmers are “trying to squeeze everything they can” out of their land. Butz has passed on, but fence-row-to-fence-row agriculture — and its vast environmental footprint — lives.

Article: https://grist.org/article/the-butz-stops-here/