Video by Tiffany Schilling – April, 2023

Seattle Times

Washington farmers have beef with imported meat: Food fight ensues over labeling

Thursday, April 25, 2002, 12:00 a.m. Pacific

By Lynda V. Mapes

Seattle Times staff reporter

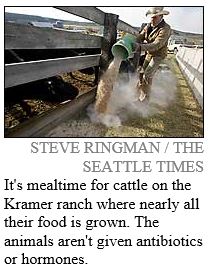

OKANOGAN, Okanogan County — Kirk Kramer noses his dad’s 1949 Chevy pickup through a river of Black Angus, worrying aloud about beef prices, trade barriers and whether labeling meat by the country of its origin would give American farmers a better chance in the marketplace.

These days, globalization is even putting the squeeze on a guy with a 2-mile-long driveway.

Cheap foreign labor and environmental costs, trade barriers and a strong U.S. dollar have farmers and ranchers from Okanogan to Orlando struggling against a rising tide of food imports.

Given the opportunity, Kramer and independent family farmers like him are betting U.S. consumers will choose to buy American if Congress will impose mandatory new labeling laws on everything from pork chops to asparagus.

“… a single patty can contain meat from as many as 1,082 animals from the United States and abroad.”

“Most every widget and gadget in the store says where it is made,” said Kramer, who helps run his family’s nearly 9,000-acre ranch. “It seems like a no-brainer to me that people would like to know where their food comes from.”

The issue is coming to a head this week as a congressional conference committee works to find agreement on new rules for food labeling as part of the 2002 Farm Bill.

Packing houses, retailers and other food-industry giants are fighting country-of-origin labeling, which they say adds hassle and expense to a global food-production system focused on low cost and high efficiency.

“This has nothing to do with the right to know and everything about protectionists wanting to kill imports,” said Sara Lilygren from the American Meat Institute in Arlington, Va., which represents packing houses.

Cheap food imports are an important cog in what has become a global processing and distribution machine.

Nearly 42 percent of all fresh fruit consumed in the United States was imported in 2000, as was 14 percent of all fresh vegetables and melons, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A total of 16 percent of all beef consumed in the United States is imported, most of it by packing houses that blend low-cost imported beef with fat trimmings from higher-end domestic-beef cuts to produce that ubiquitous American meal, the fast-food burger.

“They just want to be able to get their meat anywhere they can, as cheaply as they can and get a bigger profit.”

“We are being killed by the hamburger market, and it is because of imported meat,” said Rod Haeberle, a third-generation rancher in Conconully, Okanogan County.

Haeberle is frank about why he wants country-of-origin labeling: “I am hoping it will put my foreign competitors out of business.”

The reason for the opposition by retailers and packing houses is simple, according to Kramer. “They just want to be able to get their meat anywhere they can, as cheaply as they can and get a bigger profit.”

But what impact a labeling law would have is disputed.

Exemptions already carved in even the more stringent version of the bill offered by Senate members mean as little as 3 percent of the beef sold in groceries would be labeled by country of origin.

That is because all food service, frozen and processed meat would be exempt from the labeling law. That knocks out most imported meat because the vast majority is beef imported for hamburger that finds its way to fast-food restaurants.

McDonald’s rocked the meat industry earlier this month with its announcement that it would begin buying Australian and New Zealand beef for burgers served in 400 of 13,000 restaurants, opening its door to beef imports for the first time. McDonald’s is by far the largest purchaser of U.S. beef, so the company’s so-called “test” purchase, destined for restaurants in the Southeast, set off alarms.

Hamburger is one of the thorniest aspects of the labeling debate.

There is no uniform tracing system in place now that would allow a retailer to know, in many cases, where the animals that make up the meat in his grocery case came from. In the case of hamburger, a single patty can contain meat from as many as 1,082 animals from the United States and abroad, according to a January 1998 study by researchers at the University of Colorado.

Opponents of labeling worry customers could be put off by disclosure of the international pedigree of some hamburger in their grocery.

“This is the farthest this has ever gotten. But I wouldn’t be surprised if the food industry doesn’t still get it stripped out.”

“What would the consumer impact be should a consumer walk into a retail store and pick up a product that says ‘Product of Canada, Mexico, and the United States’? ” asked Bryan Dierlam, director of legislative affairs for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, based in Washington, D.C.

“We want to have answers to that before this bill goes through.”

There is a lot at stake for ranchers like Kramer and Haeberle, 53, the third generation to work his 7,500-acre family ranch, a picturesque spread of grassland and sage sprinkled with bounding deer.

A post-and-beam barn at the heart of his operation, constructed nearly a century ago from giant timbers hand-hewn with a froe and secured with wooden pegs, is testimony to his family’s deep roots in Okanogan cattle country.

Haeberle’s herd of about 600 cattle will become the prime cuts of beef sold in steakhouses around the country and world. But as much as a quarter of his bottom line comes from the sale of cull cattle for hamburger — and he got more for the sale of those cattle 25 years ago than he does today.

Washington growers of asparagus, tree fruit, raspberries and other crops getting killed by imports also back a labeling law, which they say would boost the market for U.S. products.

“The ideal would be that somebody going into the store would have the same information buying an apple, a strawberry or a grape as they do a T-shirt,” said Chris Schlect, president of the Northwest Horticultural Council, which represents the tree-fruit industry in Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

Labeling produce has its own problems. Onions shed their skin, lettuce is wet and wholesalers often mix the produce they obtain before selling it to retailers, so the retailer doesn’t know for sure where every lemon, orange or mushroom they sell comes from.

Despite the obstacles, some meats and produce already are labeled on a voluntary basis. Labeling produce by country of origin is already the law in Florida, where the state has estimated the annual cost of its mandatory produce-labeling law to be less than $250,000 for the entire industry.

Washington state lawmakers passed a bill last session that requires all Washington produce to be labeled by retailers. But there is no penalty for noncompliance — Gov. Gary Locke stripped fines for failing to label out of the bill, in favor of a nonpunitive approach.

Some consumer advocates favor labeling of both meat and produce for public-health reasons.

April, 2023 – TRUTH in labeling must be a goal we strive for. Under current regulations, meat companies can import from a foreign country, but because it was butchered and packaged in the United States, they are allowed to put “Made in the USA” stickers on the package in deliberate efforts to deceive.

Caroline Smith De Waal, director of food safety for The Center for Science in the Public Interest, in Washington, D.C., said she sees no greater incidence of disease outbreaks from imported than domestic food. But when there is an outbreak of a food-borne illness, labeling would enable a quicker and more informed public-health and consumer response, De Waal said.

“The major benefit we get is a better ability to trace raw produce or meat that has been identified in a food-borne illness outbreak.”

Ultimately, the consumer group would like to see a larger labeling program that includes domestic products, with food traced all the way back to its farm of origin.

For now, just getting country of origin labeling will be a struggle, De Waal predicted.

“This is the farthest this has ever gotten. But I wouldn’t be surprised if the food industry doesn’t still get it stripped out.”

Lynda V. Mapes can be reached at 206-464-2736 or lmapes@seattletimes.com.