To learn from history you must first study it.

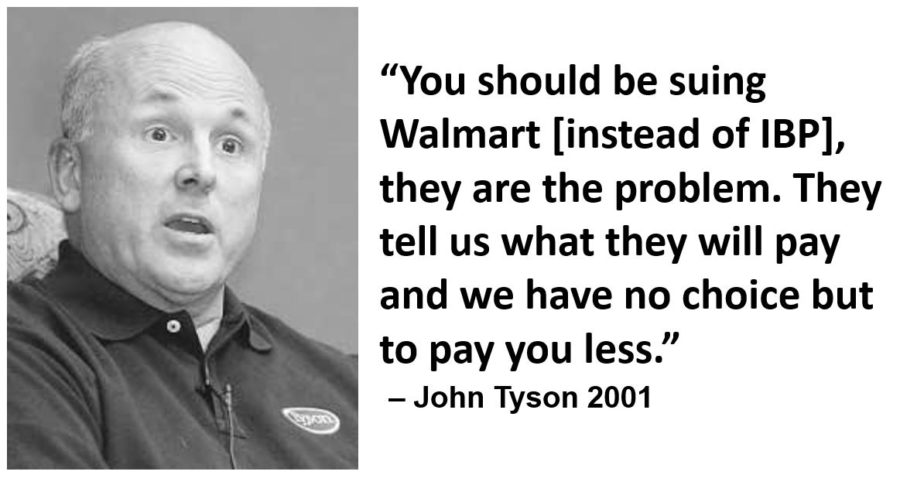

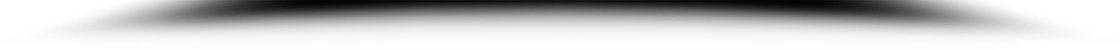

Walmart probably isn’t the best choice for cattlemen looking to align with a big retailer.

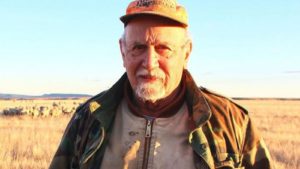

The post COVID world has exposed glaring weaknesses in our food system which no amount of marketing or smoke and mirrors can conceal. It’s now crystal clear a more decentralized local/regional food system will better serve consumers, producers, workers, the environment, and rural communities. In considering the possibilities for building new processing infrastructure, building more big plants like we have now, is not the answer. The following article about the failure of the Future Beef plant may be worth revisiting.

Since 2003, the market has become even more concentrated, with even less opportunity for new meat plant entrants to succeed. Rather than building big plants to serve the interests of big retail and big food service companies, many small, owner-operated plants that provide real food, along with food security and resilience for their communities are a far better and safer investment. In reading the following Inc. article, substitute Safeway with Walmart, a much more aggressive and even more dangerous market predator, and think about Sustainable Beef, the group of Nebraska cattle producers partnering with Walmart.

“”We knew when we started out that we were visionaries and not execution people,” he continues. “You have to know, when you’re a visionary, that you’re going to have high risk.” Bowling remains proud, but obviously defensive, in the manner of so many business revolutionaries taught sharp lessons by the marketplace when they were certain it would be the other way around.”

Failure of Genius

The founders of Future Beef were the smartest, most forward-thinking people in the beef business — and if you didn’t believe it, they’d tell you twice. So when the company went down, a lot of people wondered: How did these genius cattlemen blow it so badly?

From: Inc. Magazine, August 2003 | Page 87 By: Jess McCuan Photographs by: Livia Corona

Finally, in early November of 2001, it was time for Future Beef to celebrate. For months the company had struggled to get its first plant — a $100 million state-of-the-art beef processing operation in Arkansas City, Kansas — running smoothly. When the first cattle were hauled in for slaughter in August, parts of the plant, including the tannery and the cooking room, weren’t even built yet. And it had taken three months to get the company’s prize equipment, a multimillion-dollar dehairing system, the only one of its kind, operating to the engineers’ satisfaction. There had been problems with the dehairing chemicals (carcasses were sent, car-wash-style, through a chamber where they were sprayed with sodium sulfide) and the carcasses were coming out with hairy patches. But by November, after months of trials, beef carcasses were being successfully cooked and tanned, and dehaired in batches of 20 at a time.

It was finally time to invite the world in to see what everyone in the beef industry had been gossiping about. Two thousand people showed up to the November open house — reporters, workers, townspeople, and industry bigwigs. They listened to Future Beef’s CEO, Russell Cross, a former USDA administrator and a recent inductee into the Livestock Hall of Fame, brag that the company was finally going to “walk the talk.” The visitors were given Future Beef baseball hats and shown around a posh corporate boardroom decked out in western dé cor (“lots of leather and horns” remembers Arkansas City’s then mayor, Jerry Hooley). They sat down to a grand picnic buffet of, naturally, brisket made from cattle that had been slaughtered in the plant. Mayor Hooley, who began his plant tour feeling a bit sorry for the cows, changed his mind after he tasted the cooking room’s roast beef — “That stuff was good!”

By all accounts, the place was impressive — a 450,000-square-foot facility that represented the furthest expression of a trend in the beef industry toward fully integrated, vertically coordinated beef production. Future Beef was using sophisticated genetic data and high-tech equipment to produce massive amounts of top-quality meat, and it was a progressive employer to boot. The company offered its 900 Arkansas City workers wages and benefits that were unheard of in the industry. It had even built apartments and daycare centers for workers and their children.

“Just one month after the open house, the plant’s exclusive retail business partner, Safeway, threw up its hands.”

What the crowd couldn’t see that day was that Future Beef was already in serious financial trouble. The bottom had fallen out of the cattle market, and Future Beef was losing money on every steer. Just one month after the open house, the plant’s exclusive retail business partner, Safeway, threw up its hands. Three months after that Future Beef declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and five months after that it laid off all 900 of its Arkansas City workers. Publications like Beef and Feed Lot magazines, which had applauded the company just months before, were brimming with stories about Future Beef’s demise. When the plant finally closed its doors in early August 2002, just a year after it opened, the company owed more than $320 million to its creditors. All that remained other than the still-gleaming equipment was a spectacular case study of a business that had everything going for it except savvy.

Rod Bowling is an ideas man. According to his longtime friend and fellow Future Beef founder Rob Streight, you don’t talk to Bowling about beef without him jumping up and scribbling things out on a flip pad. Bowling, who has a Ph.D. in meat and muscle biology from Texas A&M, has held high-level R&D and administrative positions at the beef industry’s biggest plants. As he rose to increasing prominence in the industry, however, he was growing more frustrated. He was unable to get his best R&D ideas — like using organic acids as pre-evisceration washes and sorting feeder cattle into genetic groups — adopted by his employers. And so, in the early ’90s, with Streight’s help, Bowling started drawing up plans for a different kind of beef company. They made no bones about the fact that they meant to show the industry that new leadership had come along: They called their company FDR, for Finally Done Right. Later they took the slightly more demure name Future Beef Operations.

For years Bowling and Streight had been talking with other industry veterans like Darrell Wilkes, also a beef scientist by training, about how companies could produce better beef. Bowling had met Wilkes through the Denver-based National Cattlemen’s Association, a 33,000-member group that lobbies for the political and economic interests of the beef industry. The two men disagreed about minor issues, but they agreed about major ones, like the need for integration in their industry.

Integration was one of the big ideas that Bowling had been unable for years to sell to his establishment employers. (“It was too big a bite for them,” he says.) Slowly, though, the notion seemed to be taking hold. Articles in Beef argued that integration was the way for beef to take back market share from pork and poultry and a means of increasing productivity and profits. By the late 1990s two vertically integrated marketing cooperatives, US Premium Beef and Ranchers’ Renaissance, were proving that alliances between producers and packinghouses could work. Consumers also seemed pleased with what was being called the “ranch to retail” idea. It meant fewer mysteries about where their meat came from and quality checks at every step of the production process. “Our beef has a name on it,” says Ranchers’ Renaissance president and CEO John Butler. “To the consumer, that means somebody is standing behind it. The meat case is no longer just a sea of red.”

The Future Beef founders wanted this and more. Like some of the producer-processor alliances, they wanted to own and control the ranch where an animal was born, the growyard where it grew up, the feedyard that fattened it, and the packinghouse that slaughtered it — every aspect of beef production, as a Future Beef marketing slogan claimed, “From DNA to dinner.” Future Beef also wanted to make use of the entire cow, from its tongue to its tail, in “value-added” products that included pet treats, tanned hides, and variety meats (hearts, brains, and livers, sold mostly in Europe and Asia). And it wanted to outfit its plants with facilities for preparing cooked meats like pastrami, corned beef, and kabobs. Boxed beef — precut quarters of the animal that are sliced further into steaks by grocers — would be the company’s staple. But the value-added products would make it profitable. And food safety, the founders said, was a consumer right. Darrell Wilkes, who became the company’s vice president for supply, says he and the other founders intentionally overbuilt the food-safety side of things.

“Future Beef was offering workers high wages, and benefits this industry simply hadn’t seen …”

The founders had big ideas about improving the industry for workers, too. Future Beef was offering workers high wages, and benefits this industry simply hadn’t seen, like apartment housing, on-site daycare facilities, and college-credit programs for every worker. Streight, who was in charge of Future Beef’s technology, says it was central to the company’s vision: “We wanted to create an environment where people didn’t feel beaten down every day,” he says — a radical sentiment in an industry where working conditions haven’t improved much since the days of The Jungle . In most packing plants the air is oppressive and humid, in part because the water pipes (it takes a huge amount of water to run a packing plant) are usually exposed overhead and are dripping on workers. At Future Beef, all the pipes and wires were beneath the floor, and all the rooms in the plant were well ventilated and airy. Bowling himself was involved in the design and placement of the cabinets and workspaces in the plant — minimum strain, maximum efficiency — and saw to it that break rooms and bathrooms were unusually large and commodious. He also placed a full-time chaplain at the plant, available to workers going through problems on their jobs or at home.

“The real kicker in the Future Beef business plan was that it would funnel all its products to one exclusive grocery retailer.”

The real kicker in the Future Beef business plan was that it would funnel all its products to one exclusive grocery retailer. Bowling had seen it work at Keystone Foods, one of the largest processors in the business and a major supplier to McDonald’s. The idea wasn’t to build a brand for Future Beef, but to let higher-quality beef in the grocer’s meat case bring in customers for other products — “more peas and pantyhose,” says Bowling. Building a system around an exclusive retailer meant the packer had more time to tailor its products to that customer, instead of constantly switching up its product specifications to meet the needs of other customers.

By late 1996, Bowling, Wilkes, Streight, and former National Cattlemen’s Association executive vice president John Meetz had sketched out most of these ideas on paper. The group knew it needed piles of cash to make the project work, so the men began making their first cattle calls for capital. In late 1997, after they had rounded up a few initial private investors, they quit their day jobs. They recruited a CEO, H. Russell Cross, former director of the Institute of Food Science and Engineering at Texas A&M, and two financial officers, who in early 2000 helped them seal an exclusive deal with Safeway, the No. 3 grocery retailer in the country.

“The Safeway commitment came with an infusion of cash: $15 million, according to company insiders, would be added to the roughly $200 million the company was gathering at that point.”

The Safeway commitment came with an infusion of cash: $15 million, according to company insiders, would be added to the roughly $200 million the company was gathering at that point. The deal was a significant confidence booster, and the founders gave the signal to start work on the first plant. They hoped to build four or five large slaughterhouses in western cities, starting with the futuristic megaplant in Arkansas City, Kansas, built almost entirely from scratch on the site of a packinghouse.

The new $100 million plant would be named Food Engineering magazine’s 2002 plant of the year. Its dehairing equipment was the first of its kind. Developed and tested in a government lab 10 years before, the dehairing system removed hair and dirt from beef carcasses by spraying them with depilatory chemicals as they moved through a massive chamber. The system required months of intensive testing, and engineers, experts, and graduate students galore were hauled in to take their turns at mixing and pressurizing the chemicals. When the carcasses finally emerged completely hairless, says Mike Gangel, owner of the company that provided the machinery, the plant workers whooped and hollered.

“They thought at first that there was something wrong with them,” he says. “The carcasses looked so odd — they’re nude — they looked like an albino or something.”

The plant included a high-end on-site tannery. Most meatpackers, after they pull the skin off the cattle, ship the hides to third-party tanners, but Future Beef produced blue-chromed hides classy enough to be fashioned into seat covers for BMWs. The pet treats area cranked out items like Texas Toothpicks (cow tails, that is) and multiflavored cow ears. The cooking room, in the words of one visitor, “smelled really good.”

They originally called the company FDR, for Finally Done Right. Later they switched to the more demure name Future Beef.

The real pride of Future Beef was its cleanliness. At the heart of this was a ventilation system designed by award-winning engineer Chuck Pharr. The system kept microbes from flowing from “dirty” hide-and-horns areas of the plant to “clean” meat-only areas. Because the carcasses had to clear a series of food-safety hurdles, including a mild acid wash, a steam bath, and a high-pressure rinse, the plant was touted as being literally microbe-free.

The plant was essentially all it was cracked up to be. Future Beef, however, was not. The company was limping toward its August opening date.

It didn’t help that the company got into a series of protracted and expensive squabbles with suppliers. Among those was Micro Beef Technologies, developer of electronic cattle management systems. At each of Future Beef’s five feedyards, cattle were herded into a monitoring station where a feedyard operator applied conductive oil to each animal’s hide. Then, using a hand-held transducer not unlike the instrument doctors use on human patients, the operator could measure, within seconds, the density of the animal’s muscle and fatty tissues. These numbers helped Future Beef and the feedyard determine the optimal date at which the animal would be shipped off to slaughter. Micro Beef’s owner, Bill Pratt, claims two of the feedyards were using his systems long before they partnered up with Future Beef, and that Future Beef copied his systems for its other three feedyards without paying him or asking his permission. Future Beef didn’t settle with Micro Beef until after Future Beef declared bankruptcy.

Future Beef also warred with Supachill, the maker of the plant’s flash-freezing system. Future Beef intended to flash freeze parts like kidneys and tongues, but it never managed to get the equipment working correctly, and again, the tiff with Supachill resulted in a long legal battle. Supachill’s Brian Wood says the company was arrogant enough to try to operate his multimillion-dollar equipment without asking his advice.

Future Beef’s real albatross, says Darrell Wilkes, was an expensive computer system that ran enormously complex software from J.D. Edwards. “We were pouring all this data in, but we could never get the data out,” says Wilkes, whose job, as the company’s cattle and supply expert, was to monitor the progress of about 300,000 head of cattle. And these weren’t just any cattle. These were Future Beef cattle, raised by ranchers who met its standards for feeding and monitoring their herds. Wilkes had to keep track of which steers had been given certain region-specific mineral supplements, which had been fed their necessary doses of vitamin E, which had been measured for yields of particular tissues and fats, and what the optimum dates were for shipping each steer off to the slaughterhouse.

Future Beef hadn’t hedged its cattle. It couldn’t withstand losses of up to $240 a head.

When Wilkes asked his staff for the numbers, they didn’t have a clue. They had not been able to retrieve the data from the computer system.

“I swore a lot, and jumped up and down a lot, but it didn’t do a lot of good,” he says. “We would have been better off going in there with a very simple system. At least the simple systems give you your damn yield report.”

Outside auditors later came to Rob Streight to ask why the company didn’t choose a simpler system. “Well,” he said, “I built this system planning for 2.5 million cattle and five plants with 10,000 employees.” This same reasoning led Future Beef’s founders to hire a thundering herd of corporate executives, whose offices were miles from the Arkansas City plant, in Parker, Colo. If the next four processing plants were to be built in more traditional cow towns like Denver or Fort Worth, a centrally located corporate office made sense.

When the first cattle finally arrived in Arkansas City on August 8, 2001, the management team at Future Beef breathed a huge sigh of relief. Wilkes and his crew had managed to struggle through. (At one point, he told his beleaguered staff, “We’re going to do this on our own, with Excel spreadsheets and a Big Chief tablet.”) Within a few hours, hundreds of carcasses were zipping around the factory production chain, and they continued to move through for several weeks while installation crews milled around inside the plant. According to Future Beef insiders, Safeway for weeks sent reports back that customers in its Phoenix stores loved the new products, and as early as the first days of September, though the cattle market was a little bit soft, Safeway was encouraging Future Beef’s top brass to think seriously about the second, third, and fourth plants. The timing seemed perfect on the food-safety side of things — E. coli scares in the United States and breakouts of mad cow disease in Britain in the late ’90s had Americans nervous about buying beef.

Then the September 11 terrorist attacks sent an already faltering cattle market into a downward spiral from which Future Beef Operations would never recover.

Rod Bowling knew that things had not gone perfectly up to that point. The start-up had cost more — by some accounts, $20 million more on equipment costs alone — than the company had originally intended. There had been minor hiccups, like malfunctioning equipment, and major hiccups, like the lawsuits and the strain caused by the internal data system. Nothing, however, had Bowling so down as the look of the financial reports after the terrorist attacks sent the beef market to the swamp.

“Fall apart isn’t the right way to say it, although that’s what happened,” says Bowling. “It wasn’t apparent on any one day. It was more like death by a million cuts.” The cattle market had gone from highs the summer before to lows in October and November, by which time most cattle-buying operations were losing up to $100 per head on steers. And unlike other outfits, Future Beef had a long list of extra costs to account for. Because the Arkansas City plant was located at least 180 miles, and sometimes up to 275 miles, away from its high-tech feedyards, inbound freight costs were between $17 and $18 per head, compared with an industry standard of between $8 and $10 a head. Dehairing increased production costs by $3 a head. The tannery, pet treats, and deli meats areas had all been running in the red.

Worse, Bowling knew Future Beef hadn’t really hedged its cattle investments. Besides having bought cattle when the market was at a record high, Future Beef had bought animals at lower weights than normal and had kept them in growyards and feedyards longer than the normal period of approximately 150 days. This gave the company ultimate control over their nutrition and health regimens, but it also ratcheted up Future Beef’s risk. “Feeding a bull for 200 days is risky,” says Bowling. “We knew we had a tremendous risk on the cattle, but then again, we thought we were changing the business.”

The company had only one form of protection, a risk collar clause in its contract with Safeway. If Future Beef lost more than $50 per head on the cattle, the clause called for Safeway to step in and pay the difference. For three months, as Future Beef’s losses mounted, Safeway paid up. By December 2001, however, Safeway was refusing to pay. According to court documents, by the time Future Beef liquidated in August 2002, Safeway owed the company more than $13 million in collar money.

A Safeway spokesman refused to comment for this story, and referred Inc. to Safeway’s 2001 annual report, in which it stated only, “[Future Beef’s] processing plant began operations in August 2001 and failed to meet performance expectations.”

Bowling says Future Beef probably could have sustained a $50-per-head loss, but it couldn’t withstand losses of up to $240 a head. “It was $80 million and that was all we had,” he says, passionately. “Safeway could have taken that hit, but we couldn’t. The big brother in the partnership has to carry the water.”

“I had to stop concentrating on genetics and worry about how to pay the bills.”

In December, just five months after the plant opened, Russell Cross stepped down as CEO, and Thad York, a Future Beef board member and former TCI cable executive, was given control. York, whom many in the company regarded as an outsider, began cutting costs, which meant he fired the company’s legal counsel and financial officers, and later he turned off the cash-intensive dehairing machines. Priorities shifted. Ronnie Green, a beef cattle geneticist who had been reporting to Darrell Wilkes, said, “I had to stop concentrating on genetics and worry about how to pay the bills.”

Future Beef declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in March 2002, and in July it made a last effort to repair its relationship with Safeway. That same month, another major beef producer, ConAgra Beef Co. in Greeley, Colo., recalled 18.6 million pounds of beef it suspected was tainted with a deadly strain of E. coli bacteria. It was the nation’s second-largest meat recall ever. Green says Future Beef went to Safeway touting Future Beef’s impeccable safety record, to no avail. “We went to them and said ‘Look what’s happening at ConAgra — we need this many more pennies per pound to make a safe product,’ and their response was, ‘We can’t really do that.'”

In April, York fired Bowling, the company’s first founder. (“I’m still not over that yet,” says Bowling.) Morale at the plant started to slide. By June, York had fired many of the founders, many of whom had lost a great deal of personal wealth in the game. Streight says each founder contributed at least $100,000 — “which is a lot for some of us,” he says. “I’ve got my house up for sale because of it, but now I’m employed again and I’ll make it. The people who were really hurt were the employees in the plant.”

On August 7, plant manager Randal Garrett laid off the remaining 700 plant workers; more than half of them, he estimates, were Mexican immigrants or hailed from other states. Gabe Briseño left a job at a beef processing plant in Amarillo, Texas, to come to Future Beef because his wages there, as a fabrication manager, would be about $6,000 a year higher. Until August 2002, Briseño lived with his wife and two toddlers in the 120-unit MeadowWalk Apartments complex Future Beef built for its workers. When he got laid off, he moved back to Amarillo. When he heard a few months later that Future Beef’s new owner, Creekstone Farms, was hiring, he hightailed it back to Arkansas City and MeadowWalk, where his children have a swimming pool and several jungle gyms to choose from.

Future Beef didn’t use many locals for construction work, but it did hire Mell Kuhn, who runs a plumbing and heating business out of a sheet-metal building. Kuhn, an outspoken man who keeps two hunting rifles leaned up against one wall of his office, says he secured several contracts totaling approximately $350,000 to help Future Beef build its state-of-the-art water-treatment lagoon. When the company went under, Kuhn says, he was left with unpaid bills totaling $140,000.

“I accepted the risk,” he says. “I’m a big boy. But we’re just people working for a living. We’ll never see a nickel of that money.”

Future Beef’s jewel of a plant didn’t sit empty long. In January of this year, Kentucky-based Creekstone Farms formed a joint venture with the Bank of Nova Scotia, a $183 million investor in Future Beef, and the two bought the plant and all its equipment off the auction block for $42.7 million. Creekstone planned to hire back around half of Future Beef’s workers, but it would process only 1,000 head of cattle a day instead of the 1,600 the plant was built for. All its cattle would be premium black angus, to be sold mainly as a niche-market product to high-end retailers across the country.

At the plant this spring, the new Creekstone crew, including general manager Kevin Pentz and COO Bill Fielding, a former president of commodity beef giant Excel, were still scratching their heads over some of Future Beef’s business strategies.

“They were trying to do too many things that hadn’t been proven,” Fielding said. “It’s fine to test new systems, and we will do that, but step by step so that we don’t risk the whole operation.”

Fielding says Creekstone had no intention of signing up a single retail partner and no plans to use any of Future Beef’s extras, like the Supachill and dehairing equipment. It will not make blue-chromed hides or pet treats. “Boxed beef,” said Pentz, pointing to the plant’s fabrication room, where Creekstone workers in sock caps and bloody smocks sorted through piles of what would soon be flank steak. “This is the bread and butter, not pet treats and toenails.”

At the plant, rooms full of expensive equipment, including a $140,000 tenderness-testing machine and several $160,000 roll-stock vacuum-packaging units, sat idle, remnants of the reign of Future Beef. The company left behind a warehouse of unused Future Beef boxes and bags, and for a time Creekstone used them to wrap and ship some products, mostly tails and honeycomb tripe. But on this day, in an airy backroom at the plant, four Creekstone workers, armed with cloths and rubbing alcohol, sat around a long table and smeared the “FB” from every bag Creekstone planned to place its high-dollar beef in.

Since the company’s collapse last summer, many people have been willing to second-guess Future Beef, including some who were inside the company.

“There was a lot of knowledge, I would call it, but not a lot of business experience,” says Ronnie Green, who, though he is himself a Ph.D., echoes the sentiments of people inside and outside the industry who say the company suffered a classic case of Ph.D.-itis. (One investor says the joke in the industry was, “Don’t worry — if Future Beef goes under, we can always start a university.”)

It was true that many of the founders and top managers had Ph.D.s from meat-industry meccas like Texas A&M and Colorado State University, and it was also true, says Rod Bowling, that there was an “R&D mentality,” which meant people weren’t punished when certain projects failed. “In R&D, you’re mining not for the small things but for the grand-slam home runs,” he says.

Green gave up a tenured professorship in the animal science department at CSU to join Future Beef. He says he saw it as the chance to finally put all his academic theories into place. “The concept of vertical coordination, supply chain management, data to improve genetics — this was what I had been teaching my students about all along,” he says now. “And here comes this group with very good thinkers in it, who I thought had crossed their T’s and dotted their I’s a little better.”

“They questioned why Future Beef was selling a premium product to Safeway, a buyer of lower-priced “select” meats.”

After Future Beef’s collapse, trade publications and industry pundits nationwide reamed the company for everything from its pay scales to its basic principles. Many thought Future Beef had overpaid employees, from line workers to corporate execs. They questioned why Future Beef was selling a premium product to Safeway, a buyer of lower-priced “select” meats. Most agreed that carrying so much risk on its cattle was at the very least unwise.

Even more risky, critics said, was its dependence on a single customer. “I would be a little nervous about being dependent on one customer anytime,” says Curry Roberts, president of the PM Beef Group, a ranch-to-retail beef company. “Regardless of how big they are, and especially with a single plant. You’ve got to spread your risk around somehow.”

Green says the partnership with Safeway was “flawed from the beginning,” and that the language of the contract between the two companies was not clear. “It allowed Safeway a lot of loopholes, which they used, frankly,” he says. Rod Bowling says much the same thing. He also says, from the distance of his new job — he’s an employee again, at a large packer in the Midwest — that the results he was after in the Safeway deal could probably have been achieved through partnerships with a small number of retailers.

York, Future Beef’s second CEO, says that if the founders had been savvier businessmen, they would have known how to negotiate with a partner like Safeway. “In a deal like that, you either need to have a very simple contract and leave it very flexible, or you need to work out every detail and have the contract run pages and pages long,” says York. “This contract was neither of those.” York says he and other board members knew as early as September 2001, and certainly after they visited the plant in October 2001, that the company was in trouble. The reason was plain enough: “There was not enough business knowledge within the management,” he says. It’s a theme echoed in many people’s criticisms: These men knew how to manage cattle, but not capital. And they couldn’t or wouldn’t see the seriousness of that problem.

The most severe grilling the Future Beef founders ever got came in a report filed by New York – based Buccino & Associates, a bankruptcy turnaround firm hired by the Denver bankruptcy court in June 2002 to assess whether Future Beef could pull itself out of Chapter 11.

“The ability of existing management to implement the steps necessary to turn FBO around is questionable,” the report reads. “Most key functional areas are headed by people largely untrained for their tasks. The financial function is weak and data is difficult to obtain and often of questionable validity….Our observation is that there is poor coordination of effort among the senior staff, poor communication between departments, and virtually no sense of urgency within the senior staff.”

In finances, the report says, “with one exception, the entire managerial staff is inexperienced and inattentive to detail and not always accurate. The books and records of the business are incomplete and as a consequence lack total accuracy. We have had only limited success in securing reliable financial information and, to a great extent, have had to derive and/or synthesize much of the data for this report.”

“It was instead a company that burned through cash too quickly, was too pleased with itself, and failed to heed voices that urged caution.”

Bowling takes exception with some of the report. But he acknowledges that Future Beef was not a company at which things were Finally Done Right. It was instead a company that burned through cash too quickly, was too pleased with itself, and failed to heed voices that urged caution. It was a company at which, according to Ronnie Green, “the culture was ‘We have all the answers, we’ve got enough money to make this happen, and we’re going to revolutionize the industry.'”

The beef industry believed in Future Beef. Since the 1970s beef has lost ground in the national protein market to the pork and poultry industries, and it now struggles with both profitability and its public image in the wake of mad cow disease, E.coli breakouts, and Fast Food Nation . Industry leaders still hope Future Beef’s technology and parts of its business plan will appear elsewhere, but even beef’s most progressive thinkers wonder how to move past such a black eye. “Future Beef had a lot of smart people involved,” says John Butler of Ranchers’ Renaissance. “The industry will have to overcome the feeling of, ‘We tried and failed — why try again?'”

Bowling balks at the idea that people who invested in his company feel burned. “Nobody came up and chewed me out for being a stupid ignoramus who lost all their money,” he says. “Never once did I get someone who did that.

“We knew when we started out that we were visionaries and not execution people,” he continues. “You have to know, when you’re a visionary, that you’re going to have high risk.” Bowling remains proud, but obviously defensive, in the manner of so many business revolutionaries taught sharp lessons by the marketplace when they were certain it would be the other way around.

Jess McCuan is a reporter at Inc.

This blog was jointly produced with Farm Forward and authored by Mike Callicrate: a Colorado rancher, rural advocate, and owner of Ranch Foods Direct.

This blog was jointly produced with Farm Forward and authored by Mike Callicrate: a Colorado rancher, rural advocate, and owner of Ranch Foods Direct.