Following the recent collapse of our industrial food supply chain, on October 7, 2021, the House Agriculture Committee held a “Hearing to Review the State of the livestock Industry.” Chairman Scott opened the hearing with an eloquent statement of how most important and urgent it was to address issues facing our livestock sector. Then he submitted the Texas A&M report, “The U.S. Beef Supply Chain: Issues and Challenges,” which essentially says there is little problem with the current system.

Montana rancher, Gilles Stockton, along with many other independent livestock producers, see it differently:

October 21, 2021

By Gilles Stockton

Ag economists need to understand and respect the real world of livestock production.

Proceedings of a Workshop on Cattle Markets (June 2021) Agricultural and Food Policy Center, Texas A&M University

The above-named proceedings, authored by 17 economists, was obviously written to prevent the adoption of initiatives currently under consideration. Initiatives which many producers feel would improve the competitiveness and transparency of the fed cattle market. In the Proceedings first paper, by Dr. Derrell S. Peel, he starts by insulting cattle producers with the following quote from a 1999 paper by Dr. Wayne Purcell:

“The beef cattle industry is caught up in difficult times. As economic pressures intensify, reactions tend to move away from the objective and toward the emotional. Calls for solutions are becoming more strident and many are taking the form of proposed legislative remedies… The big danger is that all the attention on short-run and highly visible issues will block recognition of the problems that are long run and structural in nature and, in the process, prevent efforts to move to programs and policies that have a legitimate chance of helping.”

Then Dr. Peel goes on to write:

“The issues facing the beef cattle industry today are not new; indeed, they have changed little in the past 30 years, and some have roots that extend back over a century. It is perhaps reassuring that the industry has, for the most part, avoided embarking on policies targeting issues ‘that are more nearly peripheral in nature and often deal with the symptoms of economic problems rather that the causes’ (Purcell, 1999). Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (mCOOL) is a notable exception, but the United States did back away from the detrimental policy. However, like many other issues, mCOOL has not gone away. Indeed, the emotions, anger and frustration accompanying recent events such as the Holcomb packing plant fire in 2019, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020, and the winter storm of February 2021 have fueled demands for an array of potential legislative actions that attempt to jump to a solution without addressing the complex structural and behavioral issues that brought the industry to the current situation. The risk is that these overly simplistic solutions will have long term detrimental impacts on cattle producers, the industry, and consumers, and jeopardize the ability of the industry to compete in dynamic global protein markets for a successful future.

“There is critical need to understand why the industry has evolved to have the structure that exists today and to function the way that it does.”

The more pressing need, as identified by Dr. Purcell, is to understand and address issues “that would help the long run and structural issues that are prompting the price pressures” (Purcell, 1999). There is critical need to understand why the industry has evolved to have the structure that exists today and to function the way that it does.

The rest of the 183 pages proves beyond a shadow of the authors’ doubt that supply and demand market forces explain all price discrepancies; that increased levels of “spot” market sales will result in lower cattle prices; that Alternative Marketing Agreements (AMA) are absolutely essential to the functioning of the cattle industry; and that it is only because of the economies of scale of the packers that cattle prices are as high as they currently are. The arguments on all four of these core assertions are chock full of convenient omissions and inconsistencies.

Supply and Demand: In many places in these Proceedings it is asserted that supply and demand fully explains the discrepancies in market prices. There is not one reference to the many studies that show conclusively that with increase in captive supply (aka AMA) there is a decrease in price.

For instance, John Schroeter and Assedine Azzam, using market data from 1995/96, found that there was $1.13 per head decrease in price for each 1% rise in captive supply. That would mean that the difference in price for a 1,300-pound steer where there was zero percent (0%) AMAs and sixty percent (60%), would be $67.86. I may not be an economist but that does not seem like peanuts to me. Incidentally, Ted Schroeder and Stephen Koontz, both of whom are authors in these Proceedings, also published a study that indicated a strong negative (and statistically significant) correlation between increased captive supply and decreased prices. Somehow, they fail to take their own research into account.

Spot Market: The initiative that these economists collectively most want to prevent is the 50/14 proposal introduced by Senators Grassley and Tester. This amendment to the Livestock Marketing Act would require that fifty percent of all fat cattle be purchased through the negotiated spot market. In Chapter 3, Bastian et. al, cites an experiment done by Menkhaus et.al, which found that negotiated sales when compared to auctions resulted in prices 10% lower than optimal.

It is this that Koontz in Chapter 5 extrapolates, claiming that by mandating that 50% of the cattle are sold on the spot market, it would cost producers $2.5 billion the first year and $16 billion over ten years. But if increased use of the spot market results in lower producer prices, then why does he not recommend the elimination of all negotiated spot market sales? That would be the logical course of action, if negotiated spot markets sales cause lower prices for producers.

However, Dr. Koontz does go on to explain that use of “…AMAs do not create market power as they do not change the supply and demand fundamentals, nor do they change control of the transaction process.” If this is true, why then would increasing the numbers sold on the spot market decrease prices as he had just maintained. Would not the “supply and demand fundamentals” still be the same? Maybe it is just me, but there appears to be some confusion.

“Intuitively, most of us would agree that when one of the 40,000 or so feedlot operators negotiates with one of the 4 packers, the feedlot owner is at a natural disadvantage.”

Intuitively, most of us would agree that when one of the 40,000 or so feedlot operators negotiates with one of the 4 packers, the feedlot owner is at a natural disadvantage. Whether this results in a negative 10 percent result or not, I am not sure, but a negotiation between parties where there is a major discrepancy of power will most often result in a disadvantage to the one in the weaker position.

On a personal level, I am not a fan of the 50/14 proposal but for very different reasons. First, no one has explained how the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 can be amended to mandate that cattle sales be conducted in a prescribed manner. Second, if 50% of cattle are required to be marketed through a negotiated spot market, this implies that the other 50% will then be legally marketed through captive supply. It is my reading of the Packers and Stockyards Act that captive supplies should be declared illegal.

Alternative Marketing Agreements: Many of the words in these papers are devoted to telling us what fantastically beneficial things are these AMAs (aka formula contract and captive supply). Apparently, without AMAs, beef would be tough tasteless stuff. Listen to Senate testimony of meatpacking industry representative Mark Gardiner. They go on to claim that only through the use of AMAs can feeders get paid the true value for their cattle, because when selling through the spot market, feeders only receive average prices.

I think that cattle buyers would be bemused by this notion. Every cattle buyer with a few years of experience under their hat that I ever met always knew exactly what they were buying. Naturally, they would negotiate to pay the least possible, but if you had quality cattle to sell you would get paid for that quality. The reported negotiated spot market averages sales together, but those prices include high prices for quality cattle and lower prices for lesser quality. The notion that feeders can only be paid for their quality through AMAs is ludicrous. If this is the case, how does one explain that the use of AMAs are highest in Texas, which has the lowest quality cattle, and the least used in Nebraska, which has the best.

“It may be that these economists are in danger of confusing correlation with causation, a sin, economists in general, delight in accusing others.”

The other questionable assertion is that it has been the use of AMAs that has driven the improvements in beef quality. It may be that these economists are in danger of confusing correlation with causation, a sin of which economists in general delight in accusing others. Seed stock producers would certainly make a strong argument that it has been the adoption of EPDs and embryo transfers that has resulted in a rapid and significant improvement in the quality and uniformity of the U.S. cattle herd.

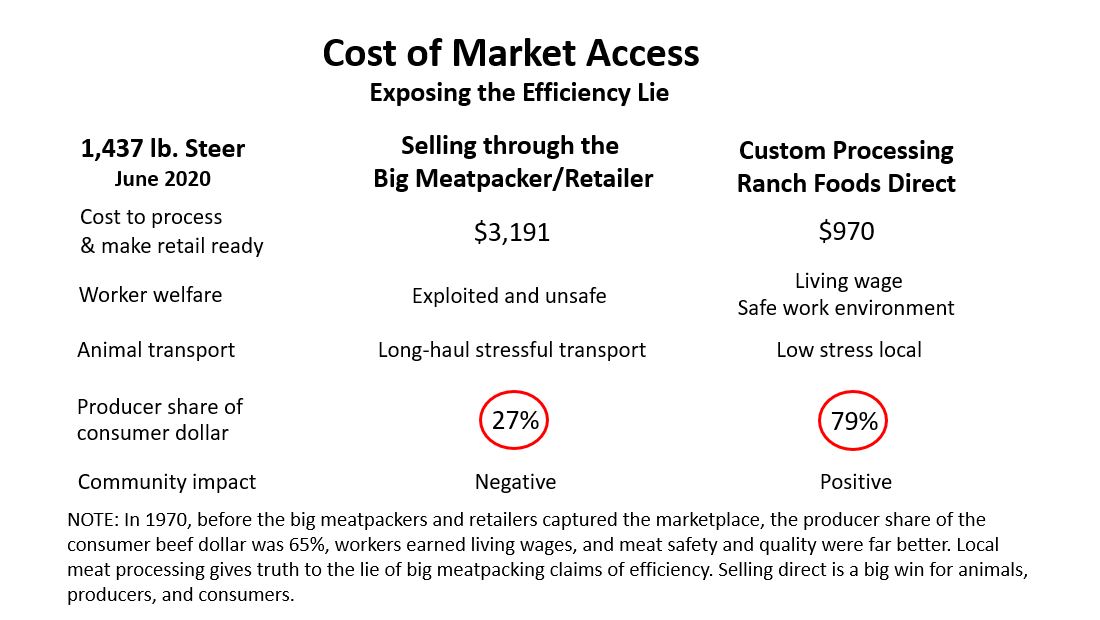

Economies of Scale: Another claim by Koontz is that producers benefit from the economies of scale of the large packing plants. He shows that there is a $20 per head difference in efficiency between a plant that can slaughter 70,000 head per month versus one that processes 140,000. Apparently, the smaller of the large plants can kill for about $200 per head while the very largest for $180. Dr. Koontz’s goes on to assert that producers are the financial beneficiaries of these economies of scale, and that this benefit outweighs whatever benefits might accrue from better market competition. He does not, however, explain why owning 10 or 20 of these large packing plants, as is the current practice with the dominant packers, is necessary. The economy of scales that he describes are only for operating a single plant.

Incidentally, my neighbor who operates a custom-exempt slaughter facility, charges $120 for killing, chilling, and aging a steer. Chances are for another $60 I could talk him into cutting it into chunks and dropping it all into a box.

Addressing the Complex Structural and Behavioral Issues: The authors complain that cattle producers are not “…addressing the complex structural and behavioral issues…” and that “… overly simplistic solutions will have long term detrimental impacts on cattle producers…” However, in the entire 183-page document there are only three half-hearted attempts to identify and address what are, in their estimation, the “structural and behavioral” issues.

In Chapter 6, Maples and Burdine question the need for maintaining the confidentiality of the packers in reporting sales and make a case for increased reporting. Maples and Burdine also like the idea of a published library of contracts. This would allow feeders to understand the deals being offered to other feedlots. Senator Deb Fischer of Nebraska has introduced the Cattle Market Transparency Act which addresses both of these issues.

Bastian et. al. in Chapter 3 reminds Dr. Peel that he had written in 2020 that “…adding a transparent electronic trading platform for spot market transactions could improve price discovery for fed cattle markets with even a small amount of transactions.” Bastian et. al. goes on to say, “We extend that suggestion here as an alternative for consideration to policies focused on mandating increased negotiated cash trade. Research suggests that a double auction would likely be the best trading institution for such an endeavor (Menkhaus et. al., 2003). Price discovery will tend to be efficient in this institution provided a sufficient number of buyers and sellers participate.”

What Bastian et. al. are proposing has already been proposed, and all of the other economists featured in these Proceedings should well be cognizant of this proposal. However, they somehow fail to mention it. In 1997, the Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC) petitioned the Secretary of Agriculture for rule making that would require that all fed cattle transactions be transparent and competitively priced. In 2007, Senators Tester and Grassley picked up the concept in their Captive Supply Reform Act.

“Competition was restored to the cattle market until the Reagan Administration stopped enforcement of the P&S Act.”

This approach is similar to that of the original Consent Decree accompanying the passage of the Packers and Stockyards Act in 1921. At that time, the packer cartel owned the market place. As a result of the Consent Decree, they were required to purchase their cattle through a third-party marketing system. It worked. Competition was restored to the cattle market until the Reagan Administration stopped enforcement of the P&S Act.

We have a similar situation today, because the packer cartel has de facto ownership of the fed cattle marketing platform. Therefore, the same solution should apply. Packers should be required to make their purchases through a third party operated market. The WORC/Captive Supply Rule would require that all AMA contracts have a base price set at the time of initiation which would be subject to a premium or discount when delivered. This approach maintains all of the benefits said to accrue to the use of AMAs, while providing full transparency and optimum price discovery.

Country of Origin Labeling: Dr. Peel goes out of his way to disparage mandatory COOL and appears relieved that it was rescinded. However, he does not explain why he feels that it is beneficial to the U.S. cattle industry to have consumers believe that they are buying beef born, raised, and processed in the USA when it in fact comes from Brazil.

Final: Since these economists prefaced their papers by insulting cattle producers, perhaps it is only fair that a cattle producer concludes this review of their work with blunt candor. When Land Grant university economists come out from behind the security of their tenured publicly subsidized positions, such that their paychecks are subject to the uncertainties of supply-and-demand market forces, then they will earn the right to lecture those of us who do.

Gilles Stockton

Grass Range, Montana