May Judge Strom rest in peace.

Judge Lyle E. Strom died on Dec 1st, twenty years after his landmark decision to reverse the $1.28 billion jury verdict in the cattlemen’s case for fair markets, Pickett vs IBP. Between the filing of the case in 1996 and the trial date in 2004, IBP, the biggest beef packer in the world, was purchased by the largest poultry company, Tyson Fresh Meats. Any chance for injunctive relief, which was crucial to keeping ranchers ranching and independent feeders in business, was lost with the reversal. Members of the jury apologized for the low monetary award, but they couldn’t justify more monetary damages due to Strom’s limiting of evidence and his jury instructions, which ran counter to the provisions of the Packers and Stockyards Act.

On April 23, 2004, the judge presiding over the case overturned the verdict, claiming the jury was required to find Tyson had a legitimate business justification for its conduct.

“The Packers & Stockyards Act prohibits unfair market conduct, and price manipulation,” said Mudd. “Congress included no language allowing unfair practices or price manipulation if the packer has a good reason for doing so. Producers must now work through the state legislatures and federal Congress to return fairness to agricultural marketing.”

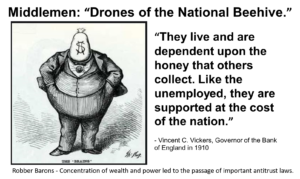

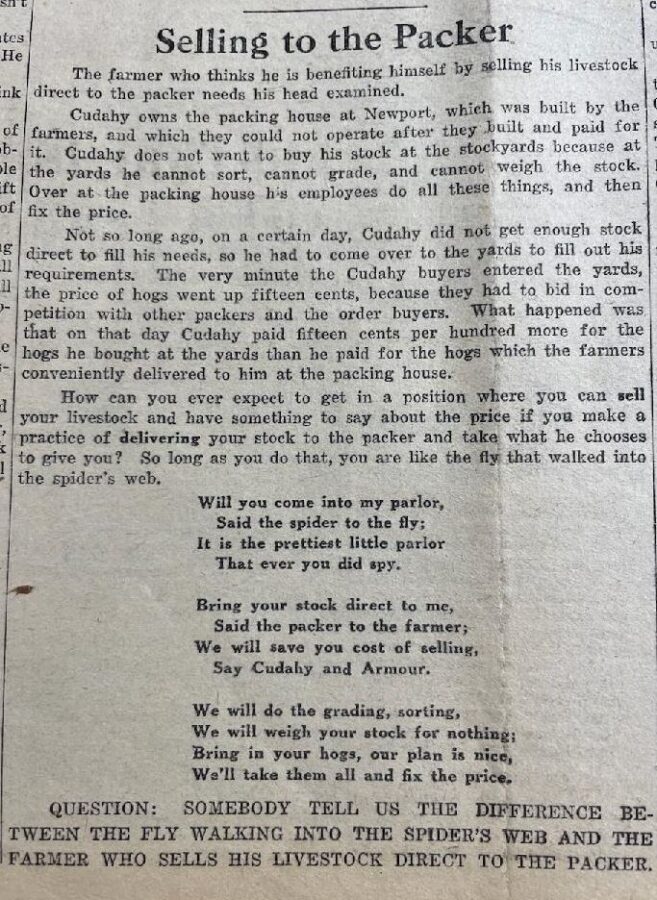

The verdict could have been the first step in reversing the anti-competitive practices in the most highly concentrated meat industry in history. Instead, Strom’s reversal of the verdict gave the green light to the meatpacker cartel to continue their pillaging and plundering of the livestock industry, bringing deeper poverty to rural America, higher prices for lower quality food to consumers and heightened risk of food insecurity in the future.

Judge Strom was a 1985 Reagan appointee in the District of Nebraska. Like many of Reagan’s appointees, Judge Strom’s decision in the Pickett case was consistent with the former president’s view on the role of government — “Government is not the solution to the problem: government is the problem.” (Inaugural Address – 1981). The over simplistic belief in deregulation led to a complete lack of anti-trust enforcement and today’s unprecedented concentration of wealth and power.

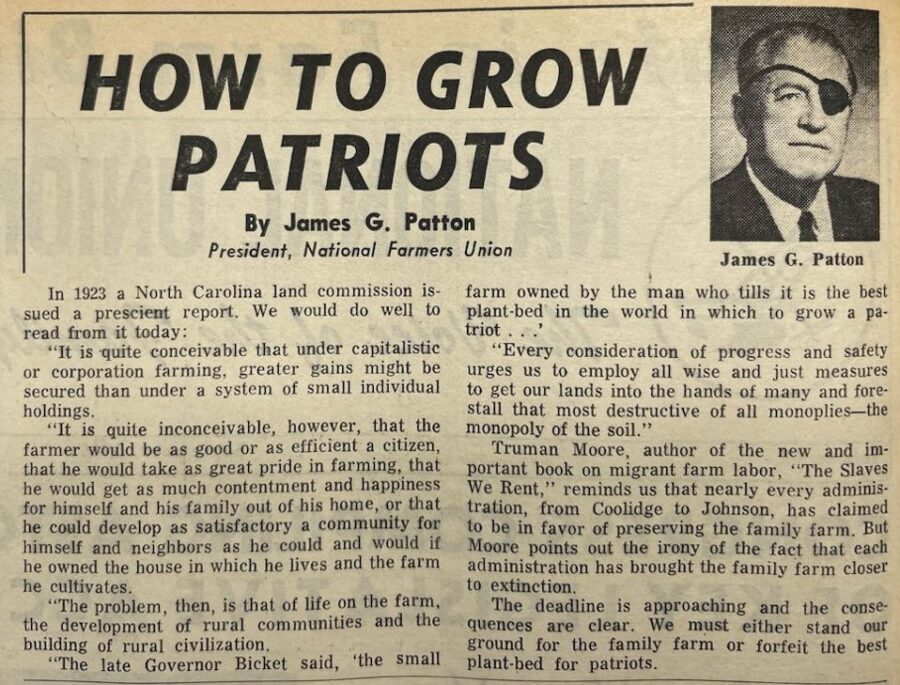

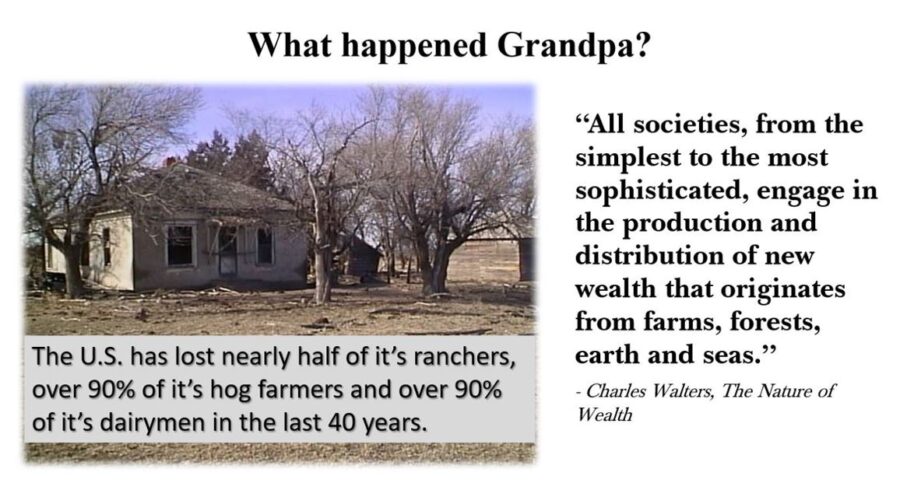

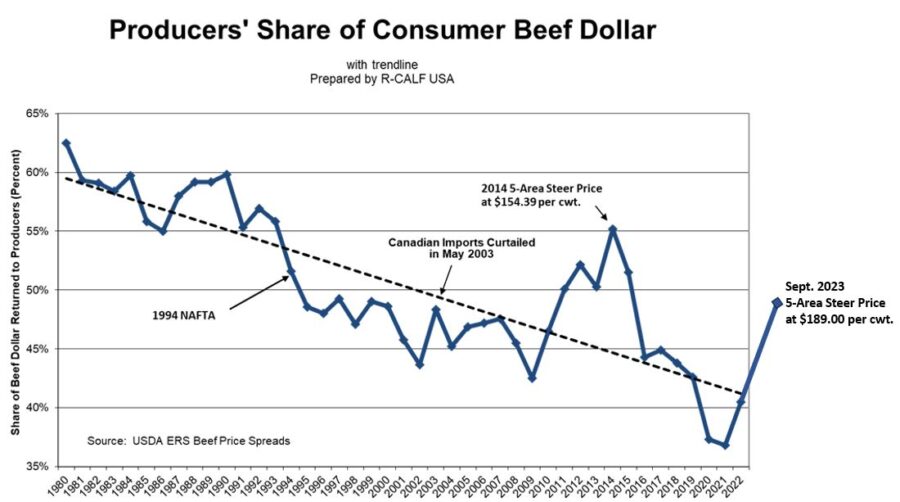

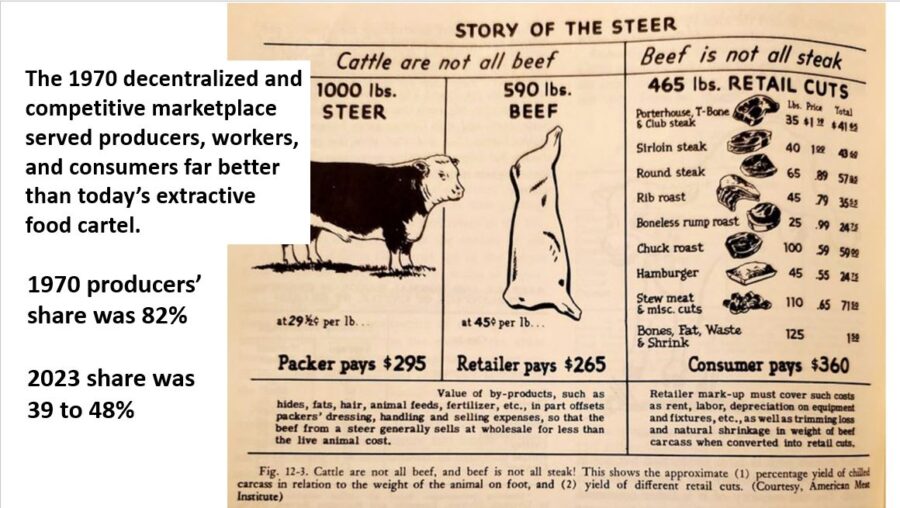

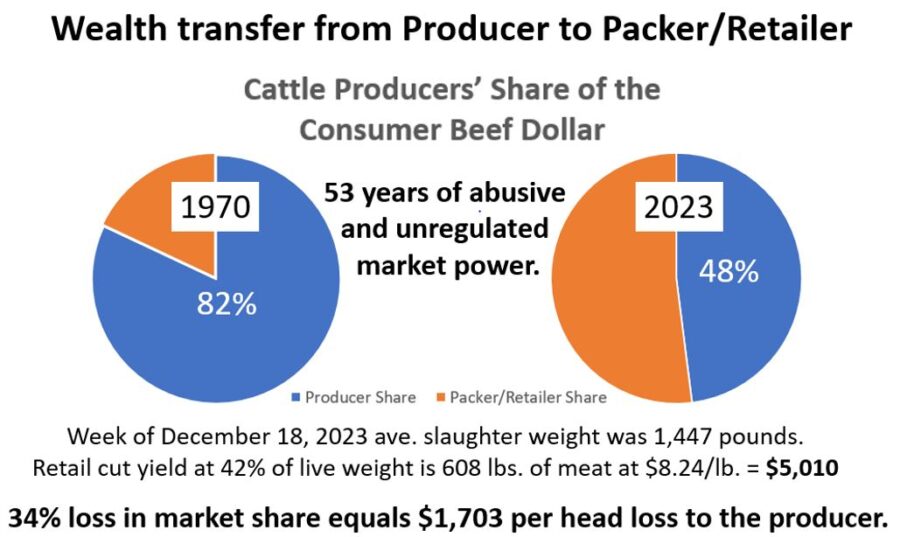

Instead of Pickett restoring the producer’s share of America’s food dollar, farm and ranch income has continued to decline as costs increase and share of the consumer dollar declines. Metrics of rural poverty are now worse than urban centers, with corporations still strip-mining resources and gutting rural communities. Dollar stores have moved in and are feeding off once-vibrant rural communities, while distributing bad food and other waste from the extractive big-box Walmart economy.

“Justice Roberts and his big business friendly court decided to hear the Anna Nicole Smith family feud case instead.”

Instead of our wealth creating farmers and ranchers making their living through competitive markets, with many buyers and many sellers for the commodities they produce, the remaining few have become serfs on their own land, or on the land of someone like Bill Gates. Government subsidies continue to make up for a growing portion of the farm income lost to the abusive corporate power unleashed by free market, free trade-oriented judges like Lyle Strom.

Consumers are now paying twice for the food they eat – first, through the high prices paid at retail, and additionally through the taxes that fund farm and ranch subsidies. Nowhere is there an accounting of the environmental destruction of industrial ag practices, including soil loss, aquifer depletion, and air and water pollution. Nowhere is there an accounting of how the loss of independent food businesses, the deskilling of the workforce, the impact of poor-quality food and increasing poverty are affecting American’s health.

After the Strom decision and a failed appeal handed down by more Reagan-appointed judges, the Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice Roberts, declined to hear the case, which left Strom’s decision standing. Pickett was the most important food system case in nearly one hundred years. It was based on the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, which was designed to protect America’s livestock producers from the robber baron meatpackers of that day. Justice Roberts and his big business friendly court decided to hear the Anna Nicole Smith family feud case instead.

So here we are, twenty years later, and the cartel-controlled food system has become more unrestrained than ever, making us dependent on imports and devoid of the domestic infrastructure to feed ourselves. Meanwhile, the monopolistic mega meatpackers are using their ill-gotten gains to invest in fake meats and insect protein alternatives.

For more:

Who will Justice Amy Coney Barrett Represent?

December 21, 2023, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) made key procedural moves on several Packers and Stockyards Act (PSA) rulemakings by submitting them to the Office of Management and Budget for review.

There’s an economic term to describe this phenomenon, it’s called stealing.

There’s an economic term to describe this phenomenon, it’s called stealing.

$8.24 retail value:

$8.24 retail value: