The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America

George Packer

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2013

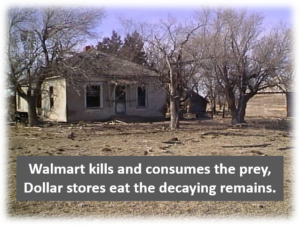

November 21, 2013 — George Packer’s The Unwinding is a minor masterpiece of the social-disintegration genre—a beautifully written, clinically observed story of the slow-rolling economic transformation that has, over the last 30-odd years, made vast parts of America into a destitute wasteland while lifting a fortunate few to a kind of heaven on earth. Following the lives of a handful of characters, Packer manages to bring together such varied phases of the disaster as the deindustrialization of Youngstown, Ohio, and the epic boom and bust in Florida real estate—he takes us, in other words, from a landmark disaster of the Carter years to a vision of bony cows wandering among abandoned suburban houses during the Obama administration. He tells us what life is like on an auto-parts assembly line; how money gets its way in Washington; and what it sounds like when a Tea Party leader contrives to kill a public-works proposal that would put her unemployed engineer husband back to work.

The book is intimate with failure but also with the libertarian ebullience felt by society’s winners. It presents an astonishing cast of characters: desperate Wal-Mart associates; firsthand observers of Wall Street’s political power; billionaire TV talkers convinced of the righteousness of the self-help gospel. Weirdly, just about everyone in the book seems to lose money in real estate. But for all their misfortunes, Packer’s people are never hopeless; they are strivers and activists and self-taught prodigies who have figured it all out—or who think they have figured it all out. Here, for example, is Packer’s description of how, after nursing quiet misgivings about the great American FUBAR, a North Carolina truck stop owner came to an epiphany one night:

He was seeing beyond the surfaces of the land to its hidden truths. Some nights he sat up late on his front porch with a glass of Jack and listened to the trucks heading south on 220, carrying crates of live chickens to the slaughterhouses—always under cover of darkness, like a vast and shameful trafficking—chickens pumped full of hormones that left them too big to walk—and he thought how these same chickens might return from their destination as pieces of meat to the floodlit Bojangles’ up the hill from his house, and that meat would be drowned in the bubbling fryers by employees whose hatred of the job would leak into the cooked food, and that food would be served up and eaten by customers who would grow obese and end up in the hospital in Greensboro with diabetes or heart failure, a burden to the public, and later Dean would see them riding around the Mayodan Wal-Mart in electric carts because they were too heavy to walk the aisles of a Supercenter, just like hormone-fed chickens.

I admire the understated horror that runs through passages like this one, and there are many of them in The Unwinding, as Packer reports on the slow decay of the industrial Midwest, or describes the moment when a good political soldier finds out that the investment banks of America are “technically insolvent,” or tells us about the newspaper reporter who stumbles upon the big story behind the housing bubble only to discover that nobody cares about journalism anymore.

How many books have been published describing the destruction of the postwar middle-class economic order and the advent of the shiny, plutocratized new one?

This is a powerful and important work, but even so, I can’t help but think that it has arrived very late in the day. Ask yourself: how many books have been published describing the destruction of the postwar middle-class economic order and the advent of the shiny, plutocratized new one? Well, since I myself started writing about the subject in the mid-1990s—and thus earned a place on every book publicist’s mailing list—there have been at least a thousand, not counting the various management texts and libertarian sermons in which the advent of that new economy is not awful but magnificent! Glorious! An ideal toward which humanity must strive with our every muscle!

Let’s list some of them. There are the “Greats”: Paul Krugman’s The Great Unraveling, David Stockman’s The Great Deformation, Niall Ferguson’s The Great Degeneration, Timothy Noah’s The Great Divergence, Robert Scheer’s The Great American Stickup, and Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation, which should probably be included despite the author’s ultimate optimism.

There are the “Ages,” such as Jeff Madrick’s Age of Greed, Thomas Edsall’s The Age of Austerity, Sean Wilentz’s The Age of Reagan, and The Age of Turbulence, which gets honorable mention because of the great success enjoyed by its author, Alan Greenspan, in screwing the world. There are the “American” tragedies: The Betrayal of the American Dream, The Looting of America, Third World America, and Why America Failed. There are nightmares of falling, like Freefall and Falling Behind. There are weird echoes from one title to another, for example from James K. Galbraith’s The Predator State to Charles Ferguson’s Predator Nation; from Donald Barlett and James Steele’s America: Who Stole the Dream? to Hedrick Smith’s Who Stole the American Dream?; and (please note that I am not complaining here) from my own What’s the Matter With Kansas? to Joan Walsh’s What’s the Matter With White People?

There is the scream-therapy approach—Beyond Outrage, Greedy Bastards. There is the voice of cool reason: The Shock Doctrine, Winner-Take-All Politics. There are the clever titles—Down the Up Escalator—and the genius titles, like Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia. And there are, finally, the classics of the genre, like Tom Geoghegan’s Which Side Are You On? (from 1991) or Christopher Lasch’s Revolt of the Elites (from 1995) or the granddaddy of all inequality reporting, the New York Times’ Downsizing of America (a high-profile series that ran in the paper of record in 1996).

Two things need to be said about this tsunami of sad. First, that the vast size of it, when compared to the effect that it has had—close to nothing—should perhaps call into question the utility of journalism and argument and maybe even prose itself. The gradual Appalachification of much of the United States has been a well-known phenomenon for 20 years now; it is not difficult to understand why and how it happened; and yet the ship of state sails serenely on in the same political direction as though nothing had changed. We like to remember the muckraking era because of the amazing real-world transformations journalism was able to bring; our grandchildren will remember our era because of the big futile naught accomplished by our prose.

The other point I want to make is that, with a few exceptions here and there, the components of this genre have been pretty damn dull. Only a few authors have bothered to approach the disintegration of America in an innovative way. There is Barbara Ehrenreich, who worked crappy jobs incognito to write Nickel and Dimed. There’s Jeff Madrick, who tried to capture the spirit of the last few decades through short biographies of financiers and politicians in Age of Greed. And then there was Deer Hunting with Jesus by Joe Bageant, a wrenching, Agee-style account of red-state poverty that received virtually no attention in the United States.

George Packer aims high with The Unwinding. His plan is to mold the raw material of journalism into the form of a classic of modernist fiction, John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, which was published in stages from 1930 to 1938 and sought to render the experience of an entire era in prose. In those days, Dos Passos was most famous for his stylistic innovations: he told the story of the country not only by following the lives of fictional characters—all of them either failures or frauds, dragging each other down the road to hell—but also with chapters made up of artfully arranged song lyrics and newspaper clippings; profiles of famous people, told in blank verse; and a “Camera Eye” section, in which the author related his own experiences in a stream-of-consciousness style. In short, the idea was to replicate the new, documentary technologies of the ’30s in a work of art.

This struck a lot of other novelists as a great idea back then. Norman Mailer, for example, adapted the techniques of U.S.A. for The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948. George Packer doesn’t adapt, however; he simply uses those techniques in exactly the way Dos Passos did. He gives us text from popular songs mashed up with headlines and bits of political speeches. The short biographies of the people who made our screwed-up world are here, too, and so are the narrative chapters, which follow three real people through their sometimes-awful lives in the same emotionless voice that Dos Passos used. Packer’s prologue, for its part, is a straight-up homage to the prose poem that begins U.S.A., in which Dos Passos wrote that Americans were only saved from solitude by the transcendent “speech of the people.” Packer comes to the same conclusion, almost exactly: “In the unwinding, everything changes and nothing lasts, except for the voices, American voices.”1

Why has Packer written such a heavy-handed homage? Maybe because our period is similar to the ’30s. Maybe because elegy and lyric, written without hope for a political rescue, are the appropriate means to describe the disintegration of middle-class America. After all, how many more books screaming about some Great Disaster being worked on the American Dream do we need? What kind of chart can an author or a blogger or a columnist present that would make the slightest bit of difference anymore? The truth is that journalism is almost completely irrelevant. And so maybe only art matters.

Photography, the movies, and sound recordings were Dos Passos’s concerns; ours would certainly include TV, the Internet, social media, maybe even Big Data.

But lifting an entire artistic formula from a novel that was popular 75 years ago seems like a peculiar way to proceed with this mission. For one thing, Dos Passos wanted to create a prose analog of the popular technology of his time (photography, movies, sound recordings), and obviously the technology has changed since then. The right way to pay homage to the great author is not to imitate his exact stylistic innovations in the manner of The Best of Bad Hemingway, but to revise it for our own age, to consider how the speech and rhythms and fatuities of our own technological time might be rendered in prose. Photography, the movies, and sound recordings were Dos Passos’s concerns; ours would certainly include TV, the Internet, social media, maybe even Big Data.

For another, Packer completely excludes from his careful imitation of Dos Passos the one element of U.S.A. that is still read and admired today: the first-person “Camera Eye” chapters. It’s a telling omission. Maybe Packer didn’t want to indulge in the narcissism of memoir—which might indeed have been unsightly in a book that is concerned so heavily with poverty and failure—but it also means that the author’s own voice is absent from the book.

Instead, this narrative of woe is told in the trademark New Yorker tone of writerly distance, almost as a form of ethnographic observation. Packer’s characters have opinions, of course—lots of them. But Packer himself seems to have very few. He tells us how Americans cope with the withdrawal of industry from their region, how they live when the only jobs they can get are at Wal-Mart, how they look when they’ve lost all their teeth. Even the period of “unwinding” itself, which has brought on the plutocratization and impoverishment and corruption that the book documents, is initially presented as just another bend in the stream of history, no different, really, from any other:

The unwinding is nothing new. There have been unwindings every generation or two: the fall to earth of the Founders’ heavenly Republic in a noisy marketplace of quarrelsome factions; the war that tore the United States apart and turned them from plural to singular; the crash that laid waste to the business of America, making way for a democracy of bureaucrats and everymen. Each decline brought renewal, each implosion released energy, out of each unwinding came a new cohesion.

Let me be blunt here: this is hollow stuff. To believe that everything will reverse itself spontaneously and yield a “new cohesion” because of some imaginary cycle of history is pure superstition. It’s a kind of middlebrow dialectic, in which the sad is eternally balanced by the happy and everything always works out in the end. Worse, it’s a species of reassurance little better than a motivational poster. Hang in there, baby—Friday’s coming!

But I believe there’s a strategy to all this. Add this oddly hopeful dialectic to the author’s way of presenting these disastrous lives without comment—as though they’re just things Americans did and said in the first decade of the 21st century—and you begin to see that these two features are what make this book suitable for a polite audience. Until now, to write about the pauperization of America has always been a political deed. This is because what Packer calls “the unwinding” was not an act of nature; it was a work of ideology. It is something that has been done to us by public officials that a lot of us voted for. Draining out this aspect of the genre is Packer’s accomplishment, the move that separates his book from the thousand similar efforts that I mentioned above. It is, strictly speaking, what makes his contribution eligible for the National Book Award while an equally transcendent book like Deer Hunting with Jesus is ignored by bien-pensant critics and prize juries alike. Packer says what dozens of others have said before, but he does it in a way that everyone can see is “art”; in a way that avoids giving offense.

Packer says what dozens of others have said before, but he does it in a way that everyone can see is “art”; in a way that avoids giving offense.

And here’s the real artifice of it all: there is simply no way Packer believes this stuff himself. He is not an indifferent or detached observer, any more than Dos Passos was. The act of describing, say, the family of luckless Floridians that the author follows from one disaster to another—this alone marks him as someone who cares, someone who doubts the official line. These people are the casualties of the coming order, whatever we ultimately choose to call it, and an author truly dedicated to that noble civilization-to-be would never bother with their story of woe and failure, whether their experiences are characteristically American or not. Indeed, for the great thinkers of the new dispensation, Americanness is itself a suspect category, a relic of the past that the holy market is quickly erasing.

To summarize: George Packer has smuggled a work of far-reaching social criticism into the mainstream by means of a thick novelistic smokescreen that has fooled almost everyone into believing they’re in the presence of art. My critical reaction to this ruse: Nice going, George Packer. If that’s what it takes to make people listen, then more power to you.

The Unwinding is a powerful piece of work, a triumph that will last long after the follies of these days have passed away and all the billionaires have entombed themselves in their icy nitro-freezers, waiting for some future civilization that loves billionaires even more than ours to come and thaw them out so they can romp and rule all over again. Reading the book makes you ache for the democracy you love, watch horrified as it dashes itself, out of a mad narcissism, against the walls of the canyon.

One of John Dos Passos’s famous passages about the “speech of the people” comes toward the end of the third volume of U.S.A., where he describes the political fight against the men “who have turned our language inside out who have taken the clean words our fathers spoke and made them slimy and foul.” And though Packer never rises to that rhetorical level, the same feeling comes through. Again and again in The Unwinding we meet characters who witness the orgy of fraud in the housing market, on Wall Street, in Washington—who watch as society’s greatest rewards are handed out to its biggest crooks—and, as Packer writes of Elizabeth Warren, were brought to “radicalism, like many conservatives …, by seeing the institutions that had sustained the old way of life collapse.” And although Packer doesn’t take the obvious next steps that Dos Passos does, there is nothing to stop his readers from arriving at Dos Passos’s conclusion: that “our storybook democracy” is long gone; that “America our nation has been beaten.”