by Gilles Stockton

Gilles Stockton

Two weeks ago it was reported that China will not impose tariffs on US agricultural imports in return for our country allowing ZTE, a huge Chinese tele-communications firm, to purchase US produced components for which ZTE was previously banned because they violated sanctions on Iran and North Korea and spied on US customers. Apparently as part of this agreement, China will strive to import more agricultural products from the US in an effort to reduce its annual 376 billion dollar trade advantage over the United States.

But everything is up in the air again as the White Houses announced last week that we will impose 25% tariffs on a number of high tech Chinese imports. It is really not clear if we are in a “trade war” with China or not but there are underlying issues that need to be resolved. We, as a nation, have never had a substantive debate over the pros and cons of the trade agreements. Public debate has been difficult because the partisans of laissez-faire free trade refuse to debate. They brand anyone questioning the trade agreements as naïve moronic protectionists not worthy of consideration. But now after 24 years of experience with NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) people have a lot of questions. Especially questions about how the trade agreements are structured and who wins and who loses.

Trade Deficit

According to the Free Traders, a half a trillion in annual trade deficits does not matter because trade is always good. They say that if China, or another even lower wage country such as Bangladesh, is willing to sell us stuff for less than we can manufacture it at home, it is like they are giving us free money. We should jump on the bargains and tell ourselves that the Chinese and/or Bangladeshis are chumps for selling things so cheap.

This misses something important because not everything one buys is actually useful. Much is simply “stuff,” purchased because it is in fact very cheap, but has no “intrinsic” productive value. Buying “stuff” you don’t really need can make you feel good but it is like throwing your money away.

“Productive” purchases on the other hand are an investment. A new truck, or tractor, or machine tool, or household appliance can potentially make you money or save you valuable time. If you habitually throw your money away, eventually you will have less money. If, on the other hand, you systematically invest your money in productive purchases, in the end, you will have more money. This is true for both individuals and for countries.

Unfortunately, our culture is addicted to shopping and this explains much of the trade deficit – we see this both in record levels of personal indebtedness and the ballooning national debt. Our political leadership structured the trade agreements to favor imports over exports.

We were repeatably promised that the outsourcing of our manufacturing capability would not matter because we will be the leaders of the “the new global economy.” That of course has proven to be not true. Our country and our people are steadily falling behind because we failed to make the educational investments needed to prepare our younger generation, or make sure that there were good jobs waiting for them.

A big problem with our government’s approach to the trade treaties is that we make no distinction about strategically important industries. We have simply outsourced the whole lot on the premise that the market will sort it out. China, however, is very strategic in its approach to trade. The term for this predatory capitalism is neo-mercantilist. If they can’t steal the technological advances outright, they insist that technology transfers be part of the cost of being granted access to the Chinese labor force and markets.

Meanwhile our wholesale embrace of outsourcing has resulted upon the US becoming dependent upon global supply chains, which when disrupted, cause wide spread economic harm. And, of course, we totally abandoned the people who once worked in those industries. By some accounts the net effect is 2 to 3.5 million jobs lost to China and another million to Mexico. The actual total is way more and hard to count because imports also creates jobs. The problem is that the “new American economy” does not pay as well as the “old.”

Strategic Industries.

This is still a dangerous world. War and environmental disasters are too common, and any country that becomes too dependent upon global supply chains is risking the lives and wellbeing of its population. There are such things as strategic industries, and our country should protect those industries from excessive and predatory competition.

Our national defense capability should of course be a protected. The viability of steel, aluminum, copper, and other metals industries is obviously important because metal is needed in so many manufactured products. It would be foolish to allow one’s entire metal refining industry be undermined by imports. Energy, electronics, aviation, robotics, artificial intelligence, and pharmaceutical production are candidates for protection. Food – any country that allows its food production capability to wither in favor of less expensive imports is putting its citizens at risk.

Sovereignty

Our sovereignty, and by extension our Constitution, has also been circumvented by the inclusion of “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” mechanisms in the trade agreements. Foreign governments and global corporations were given the right to challenge and overturn laws and regulations that the citizens of this country democratically enact. We have not even been allowed the opportunity to object.

What happened over Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) is an egregious example of how foreign governments and global corporations are allowed to interfere on our sovereign right to govern ourselves. In order to distinguish domestically raised beef, pork, and lamb, Congress, in 2002 passed a law requiring a label stating the country of origin.

The governments of Canada and Mexico, on behalf of the global meat packing cartel, challenged COOL. The issue was adjudicated by an international panel of three trade judges (one judge previously served as a trade official for Mexico). Since only government officials can address the essentially secret proceedings, representatives of the US cattle industry could not attend these hearings. Ultimately, the World Trade Organization tribunal ruled against COOL and Congress dutifully rescinded the right of US consumers to know the country of origin of their meat purchases.

This is obviously disturbing but given the secrecy in how the trade agreements were and continue to be negotiated – inevitable. The interests of the American public have been systematically excluded from participation in the trade negotiations. However, international investors and representatives of global corporations are at the negotiation table. Once a trade treaty has been negotiated, Congress is not allowed to debate the individual provisions but pass the entire treaty in an up or down vote. The process guarantees that the international trading system always favors the investor class, while undermining the rights of labor, and ignoring the environmental side-effects.

Equivalency

The laissez-faire free traders also dismiss the trade deficit on the grounds that a third to half of the total is created by domestic US companies who manufacture abroad but sell their products in America. If you are not an owner of that now global company, it cannot befit you. Most Americans, in fact, do not own stocks and therefore receive no benefit from outsourced production. A global corporation is beholding to its global investors – not to its employees, or to its customers, or to the country that initially gave it the opportunity to create its wealth.

All of the trade agreements were signed with our President at the time making lavish promises of immediate increases in exports. Time and again that proved not true because the treaties are clearly structured to favor imports. We grant trading partners favorable terms with little regard to equal access to their markets. We unilaterally dropped tariffs to nothing but still face both tariffs and non-tariff barriers for our exports. Currency manipulation to discourage imports and make exports more attractive is technically not allowed, but in practice nothing has been done to stop China from doing just that. In addition, China will not allow foreign investors to own more than 50% of a corporation. Chinese investors, however, face no restrictions when buying US corporations, including high tech companies in Silicon Valley. Equivalency, in terms of trade has not been a consideration for our government.

The VAT

Then there is an aspect that is almost totally ignored but effects everyday Americans directly – the Value Added Tax (VAT). A VAT is a national level sales tax that most countries in the world rely upon for funding their investments in infrastructure, education, and healthcare. The global average is about seventeen percent (17%). The United States is the only notable country in the world to not have a VAT. We, instead pay for infrastructure and public education through locally imposed sales and property taxes. Health care, for those fortunate enough to have health insurance, comes mostly from one’s employer.

The problem is that under the trade agreements, the VAT is refunded to the manufacturer for everything they export and imposed on all imports. For instance, a car that costs $25,000 in a foreign country of manufacture will have a net cost of 17% less ($20,750) on the US market. On the other hand, a $25000 car manufactured in the US will sell for $29,250 when exported to this same country.

Infrastructure, education, and health care must still be paid for, and if a US brand name global corporation has outsourced its manufacturing to foreign shores, that company is no longer contributing to the tax base of the US community it has abandoned. The people left behind are still on the hook, paying higher property and sales taxes for the maintenance of the infrastructure and the costs of public education. And since the “new American economy” often does not include health insurance, people struggle to pay their own health care costs.

Agriculture and the Promise of Exports

For the last half century, agricultural policy has been premised that if a farmer tilled more acres, used larger equipment, and employed the latest bio-technology, that this “efficient” farmer would prosper because of export demand. This policy worked as planned, the number of farmers since 1980 has decreased by two-thirds. Yet the surviving so-called “efficient” farmers of today find themselves perhaps even more vulnerable than farmers ever were. More land, more machinery, and astronomical operating costs translates to untenable debt.

Bigger farms of course also mean fewer farmers, and as a result the communities where farmers live and where their children attend school, are now hollowed out repositories for some of the poorest people in the nation. Rural America no longer resembles a picture by Norman Rockwell and is instead a widely disbursed slum. Too many living in Rural America are in a perpetual economic depression and anything that threatens to disrupt agricultural exports makes conditions even worse.

Unlike corn and soybeans, this country does not raise enough cattle to meet the domestic demand. As a result of the trade agreements we get high levels of beef and live cattle imports which in turn depresses domestic cattle prices. Agriculture, therefore, is not united in its opinion of laissez faire free trade. Cattle producer’s experiences with NAFTA, and the WTO are revelatory of the issues at stake.

For cow/calf producers and independent feedlot operators, NAFTA has been nothing but a disaster. Upon signing that trade agreement, all of Canada’s and Mexico’s cattle instantly became “captive supplies” controlled by the three major packers. A source of feeder and fat cattle that was invisible to the domestic market, making US cattle prices much easier to manipulate. To counter the negative effects of imports, American producers convinced Congress to pass COOL. The hope was that consumers would elect to purchased US produced product. In retaliation, the packers enlisted the governments of Canada and Mexico to use the “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” provisions imbedded in NAFTA to declare COOL discriminatory to the trading interests of Canada and Mexico.

The cattle industry also found out that International trade trumps animal health considerations. Because of NAFTA, we imported BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalophagy) from Canada and continue to import tuberculosis from Mexico. Our trade treaties with South America puts us at a high risk of importing Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD). An outbreak of FMD will devastate livestock production for decades. The trade agreements saddle livestock producers with the risks from imported diseases, while the global corporations rake in the rewards.

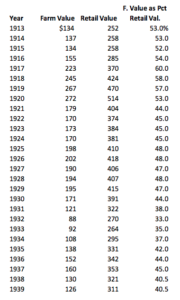

What American agriculturalists did not consider in their embrace of the imperative to “get bigger or get out of agriculture” and in the promise of lucrative export markets, is that as a consequence the competitive market for what they grew would evaporate out from under them. The “market” for all of the major commodities can no longer be called actual “markets.” None of these crops are sold subject to true “supply and demand’ in a transparent competitive market place.

Any segment of agriculture that is dependent upon exports to absorb its excess production is vulnerable to changes in demand, foreign wars, environmental disasters, and policy decisions by our own government. The Farm Bill does not even try to protect agriculture from price shocks caused by disruption in export demand. Nor do the makers of farm policy apparently care if farmers and ranchers have fair and transparent markets.

As a consequence, farmers and ranchers are no longer independent producers, selling into a free market. Instead we are serfs, contractually and financially dependent upon a handful of interlocking vertically integrated global monopolies. So, obviously, there is more to the rural economic crisis than just whether China buys American soybeans and corn. Those of us who grow food are pawns in the high stakes game of who benefits from laissez faire free trade and who loses. These are serious issues that go beyond the solvency of our farms, because the future of our country and the survival of our constitutional government is also at stake.

Lobbying by global agri-business and the farm groups that represent them target farmers and ranchers to pressure the Trump Administration to back off on the declared trade war. It hard to say what has been the effect of this lobbying, since the Administration is happily flip flopping back and forth again on the stated goal of leveling the trade playing field. Farmers and ranchers may have no influence over the market for our products but if we still have some lingering political influence, we need to stand up to the global agri-business corporations. For the sake of all Americans, the international trade regimes need reform. In the process we need a united front if we are to restore competitive markets, regain our independence, and rebuild our communities.

Conclusion

Laissez faire free trade and international trade are two different things. Trade between countries should be equivalent. If another country needs to import things that we produce and if we need to buy things that they produce, then trade in natural. The terms imposed should be equal. Safety standards, respect for labor, and mitigation of the side effects on the environment should be strong and equivalent. The rights of the citizens of all countries to govern themselves, should be protected. International trade, just like commerce everywhere should bring together willing buyers with willing sellers. Properly structured trade agreements benefit everyone.

Recent news on the NAFTA re-negotiation talks are disturbing. There are indications that our negotiators will settle far short of the desperately needed NAFTA reforms. The “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” provisions, which were employed to outlaw COOL, may not be eliminated as promised. A problem with the Trump Administration’s approach to trade reform is that we, the public, are not privy to the bottom line. There is nothing written that explains the ultimate goal. This has been the problem all along with all of the trade negotiations – it has not been a democratic process. We the people have been systematically kept in the dark with no avenue to express our opinions or desires. The result is a trade regime that has eclipsed the Constitution. America deserve transparency because it is time to take our country back.

Gilles Stockton

Grass Range, Montana

An excerpt from Whitman’s “Democratic Vistas,” published in 1871:

An excerpt from Whitman’s “Democratic Vistas,” published in 1871:

4th article, “Value-based cattle marketing dominates”, Reiman attempts to mentally condition Angus breeders and other cattlemen to accept their fate in Big Food’s supply chain where performance enhancing drugs, added flavorings, Pink Slime, various pre-digestion methods, and meat recalls, do more to damage demand than CAB quality can possibly do to help it.

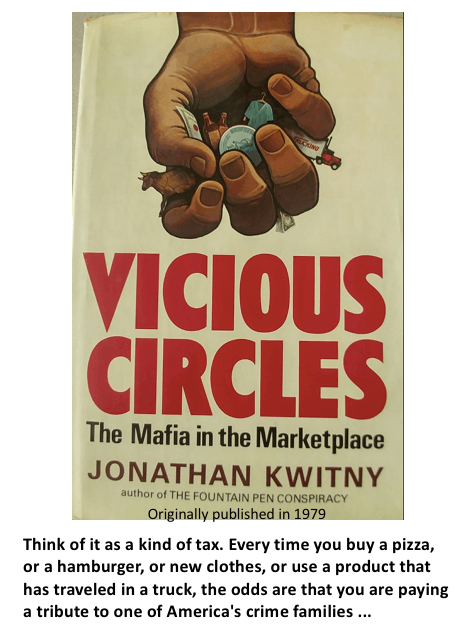

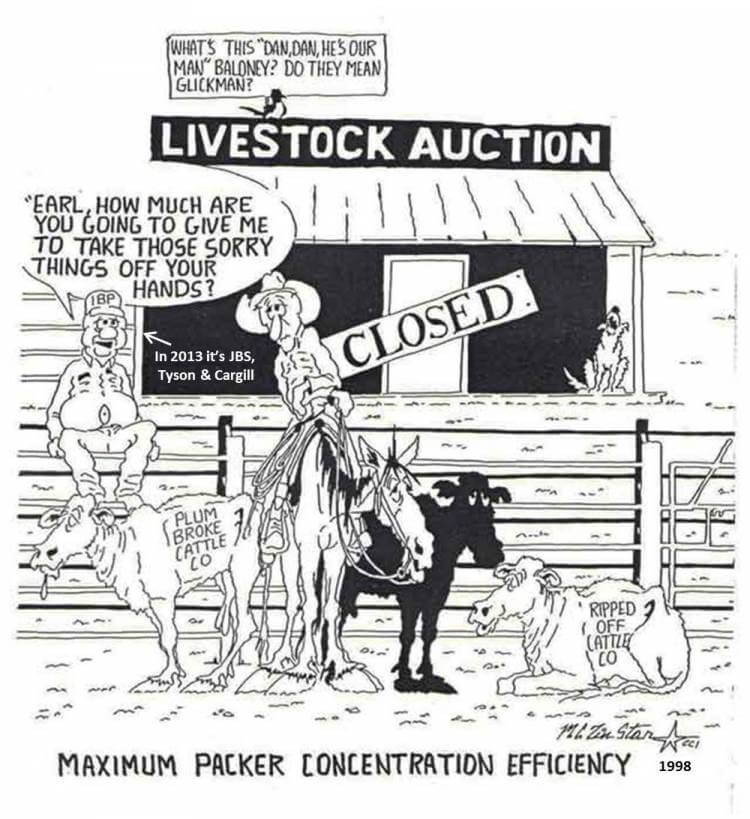

4th article, “Value-based cattle marketing dominates”, Reiman attempts to mentally condition Angus breeders and other cattlemen to accept their fate in Big Food’s supply chain where performance enhancing drugs, added flavorings, Pink Slime, various pre-digestion methods, and meat recalls, do more to damage demand than CAB quality can possibly do to help it. most of the smaller independent regional packing companies, drastically reducing competition. Additionally, they were feeding more of their own cattle and making preferential pricing and exclusive market access deals with the biggest feeders for additional large volumes of cattle that they didn’t have to bid on. Armed with enough captive supply cattle to stay out of the cash market for an extended period, the packers dropped the price of fat cattle $17 per cwt. in six weeks – a loss in value of around $200 per head. Over a thousand angry cattlemen packed the Holiday Inn in Omaha, Nebraska. The packers got the message. The market recovered about $12 per cwt. right away. The packers learned an important lesson – without competition, the market, and people’s perceptions, would have to be managed.

most of the smaller independent regional packing companies, drastically reducing competition. Additionally, they were feeding more of their own cattle and making preferential pricing and exclusive market access deals with the biggest feeders for additional large volumes of cattle that they didn’t have to bid on. Armed with enough captive supply cattle to stay out of the cash market for an extended period, the packers dropped the price of fat cattle $17 per cwt. in six weeks – a loss in value of around $200 per head. Over a thousand angry cattlemen packed the Holiday Inn in Omaha, Nebraska. The packers got the message. The market recovered about $12 per cwt. right away. The packers learned an important lesson – without competition, the market, and people’s perceptions, would have to be managed. head cattle buyer Bruce Bass admitted that IBP paid less for cash cattle when captive supplies were plentiful. Grade and yield data showed that the cash cattle IBP was forced to bid on (to set the price for captive cattle), were better quality than their so-called value-based purchases. Judge Lyle E. Strom, a Reagan appointed “de-regulation”-“bigger is better” judge, reversed the jury’s verdict, handing the cattlemen’s win over to Tyson/IBP and sticking cattlemen with Tyson’s court costs.

head cattle buyer Bruce Bass admitted that IBP paid less for cash cattle when captive supplies were plentiful. Grade and yield data showed that the cash cattle IBP was forced to bid on (to set the price for captive cattle), were better quality than their so-called value-based purchases. Judge Lyle E. Strom, a Reagan appointed “de-regulation”-“bigger is better” judge, reversed the jury’s verdict, handing the cattlemen’s win over to Tyson/IBP and sticking cattlemen with Tyson’s court costs. times the premiums, is leaving independent producers, from ranchers to feeders, with no chance for a fair price and no hope of survival. Honesty, integrity, and meat quality have disappeared along with antitrust law enforcement and a fair cash market. The retailer monopoly (Walmart, Kroger, Safeway, etc.) is charging record high prices for beef as independent producers are slaughtered with their livestock.

times the premiums, is leaving independent producers, from ranchers to feeders, with no chance for a fair price and no hope of survival. Honesty, integrity, and meat quality have disappeared along with antitrust law enforcement and a fair cash market. The retailer monopoly (Walmart, Kroger, Safeway, etc.) is charging record high prices for beef as independent producers are slaughtered with their livestock.