FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

April 25, 2019

Contact: Hannah Packman, 202.554.1600

hpackman@nfudc.org

Farmer’s Share of the Food Dollar Falls to All-Time Low

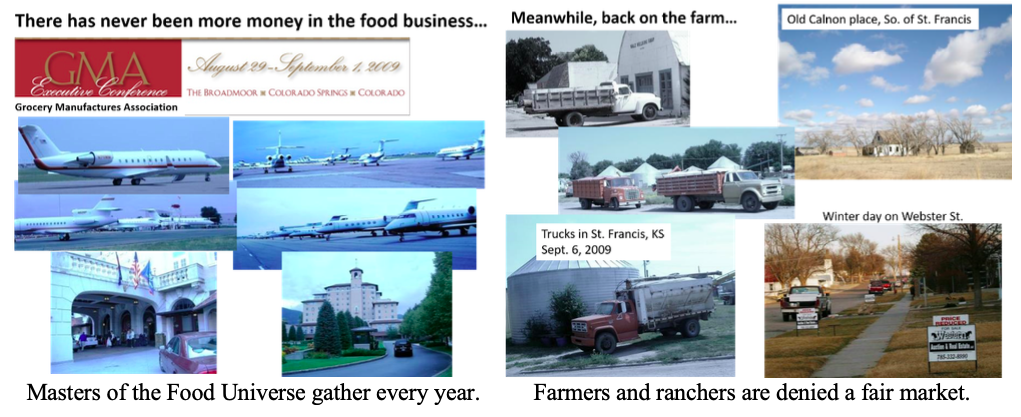

WASHINGTON – For every dollar American consumers spend on food, U.S. farmers and ranchers earn just 14.6 cents, according to a report recently released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS). This value marks a 17 percent decline since 2011 and the smallest portion of the American food dollar that farmers have received since the USDA began reporting these data in 1993. The remaining 85.4 cents cover off-farm costs, including processing, wholesaling, distribution, marketing, and retailing.

National Farmers Union (NFU), which has advocated for family food producers’ social and economic welfare for more than a century, uses the annually calculated statistic as a barometer of the state of the farm economy. In response to the updated report, NFU President Roger Johnson released the following statement:

“Even though family farmers and ranchers are more productive today than they have ever been, they’re taking home a smaller and smaller portion of the American food dollar. This one data point doesn’t paint the full picture of the farm economy, but when considered in the context of depressed commodity prices, plummeting incomes, rising input costs, and deteriorating credit conditions, it is certainly clear that we are in the midst of an agricultural financial crisis.

“Conditions for farmers have been eroding since 2011, and there’s only so much longer they can hold on. Many have already made the heartbreaking decision to close up shop; in just the past five years, the United States lost upwards of 70,000 farm operations. As a country with a growing population and growing nutritional needs, we can’t afford to lose many more. We sincerely hope this startling report will open policy makers’ eyes to the financial challenges family farmers and ranchers endure on a daily basis and convince them to provide the support they so desperately need.”

Download NFU’s Farmer’s Share

What happened to the farm share of the food dollar?

The following quote is cut in stone above the main entrance to the USDA headquarters in Washington DC:

“THE HUSBANDMAN THAT LABORETH MUST BE THE FIRST PARTAKER OF THE FRUITS.” – SAINT PAUL

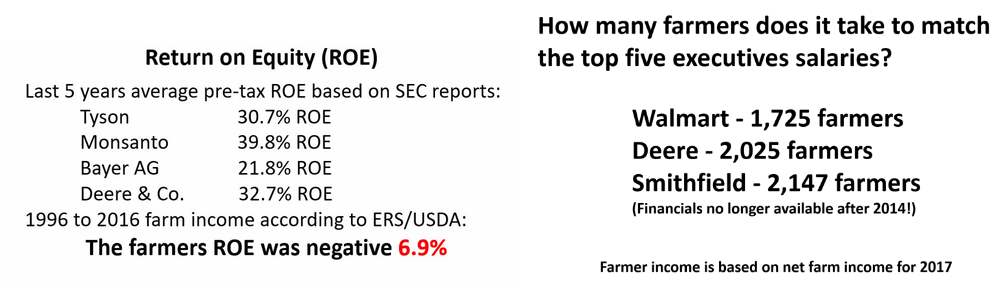

Thanks to agency capture and the monopoly power of Big Food, the husbandman is getting none of the fruits. Corporations steal the wealth of agriculture, leaving farmers and ranchers to eat their equity.

The Kansas Union Farmer: September 19, 1940

Farm Share of Food Dollar to New Low Mark

Income Gains Offset by Cut in Farm Purchasing Power Bacon to ’34 Level

The farmer’s share of the consumer’s food dollar is lower today, Farm Research finds, than before the first World war, and is in fact lower than at any time with the exception of the period of 1931-34. In June 1940, the latest date for which the U.S. Department of Agriculture series is available, the farmer’s share of the worker’s food dollar, figured on the basis of a food budget, comprising 58 representative items, was lower than in any recent year since 1934.

Farmer’s Share of Worker’s Dollar Spent for 58 Foods

1913 53c

1935 42

1936 44

1937 45

1938 40

1939 41

1940 (June) 39

This increase in the share of the worker’s food dollar going to middlemen and processors is especially significant in connection with the problem of how farm income can be effectively increased. In recent years even when cash income from farm marketings has increased slightly, the farmer’s share of the consumer’s food dollar has continued its downward trend. And the ratio of prices received by farmers to prices paid by them, i.e. the buying power of the farm dollar, has declined.

Ratio of Prices Received by Farmers to Prices Paid – U.S.D.A.

1910-14 100

1935 36

1936 92

1937 93

1938 78

1939 77

1940 (June) 77

To take certain food articles, then farmer’s share of the consumer’s pork dollar, in June 1940, was down to 51 percent, as compared with 59 percent in 1935, and 67 percent in 1937.

Forty-one percent of the dairy dollar went to farmers in June 1940, as compared with 45 percent in 1935, and 48 percent in 1937.

Only 53 percent of the egg dollar went to farmers in June 1940, though they received 66 percent in 1935 and 59 percent in 1937.

The farmer got only 36 percent of the white flour dollar in June 1940, as compared with 39 percent in 1935, and 52 percent in 1937.

Only 14 percent of white bread expenditures went to farmers in June 1940, as compared with 17 percent in 1935, and 20 percent in 1937.

Farmers got 47 percent of the navy bean dollar in June 1940, as compared with 55 percent in 1935, and 51 percent in 1937.

Fifty-seven percent of expenditures for white potatoes got to the farmers in June 1940, as compared with 42 percent in 1935 and 54 percent in 1937.

The year 1937 stands out in most of these comparisons as having afforded the farmer the largest share of the consumer’s food dollar in recent times. The income of workmen in industry also reached its post-depression peak in this same year. The buying power of the farm dollar had also reached its recent high.