The Coronavirus has exposed the abject failures of a highly concentrated and centralized industrial food system. Following is some history of how we got to this place that we can no longer feed ourselves.

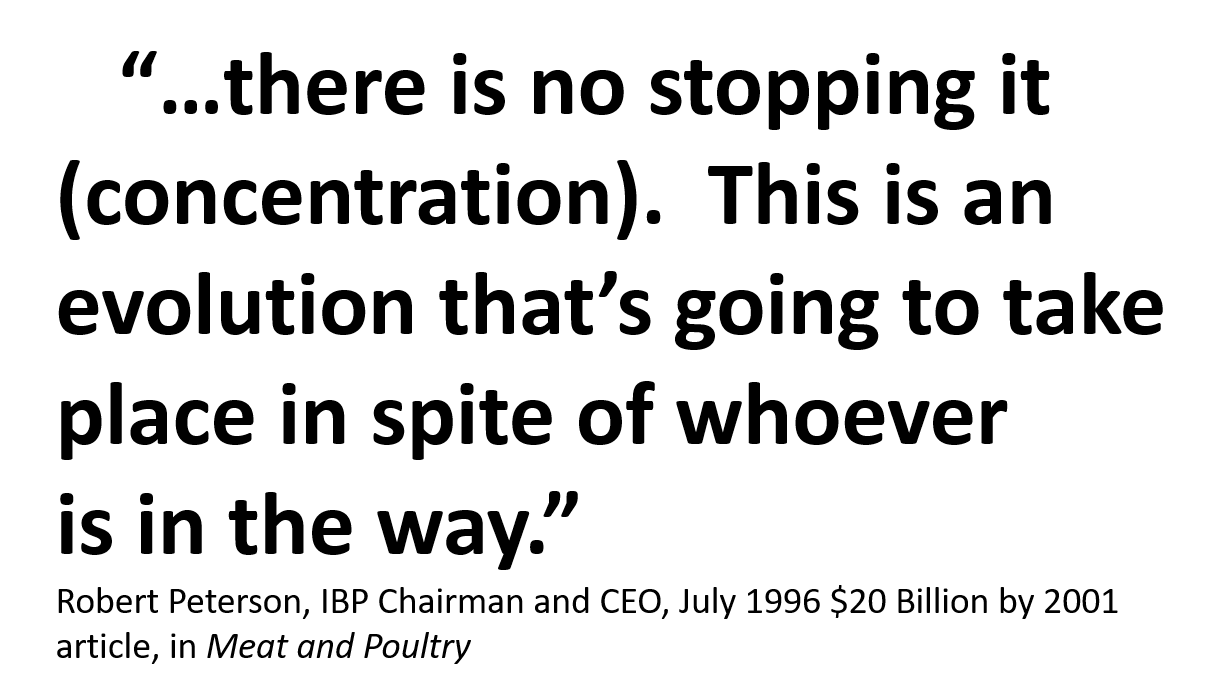

Six years after the following 1990 LA Times article was written, and after most of the competition in the meat industry was eliminated by IBP and the other major meatpackers, the confident IBP Chairman and CEO, Robert Peterson, proclaimed:

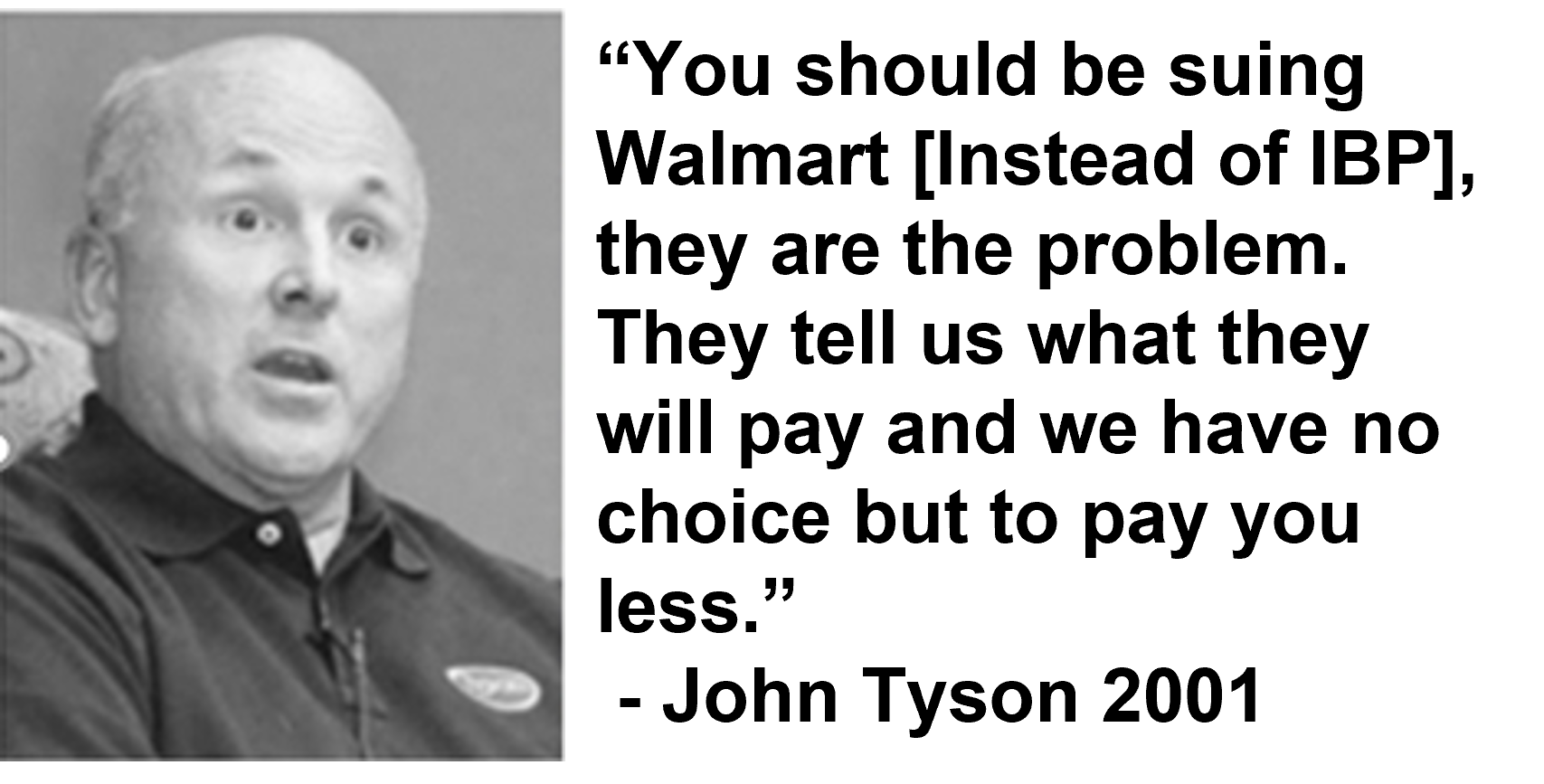

Eight years after Peterson’s bold statement, Tyson, the nation’s leading poultry company, purchased our nation’s largest beef packer and price leader, IBP. I explained the cattlemen’s lawsuit against IBP to John Tyson when we met at the 2002 NCBA convention. Mr. Tyson was there to announce that Big Chicken had just bought Big Beef!

Enter the criminal Batista brothers and JBS:

JBS Used Illegal Activity to Profit and Take Over the U.S. Beef Market

From a small butcher shop in Brazil, JBS has become the world’s largest meat processing company and a dominant force in America’s food industry, and much of its growth is the result of illegal activity.

JBS Bribed Brazilian Officials for Government-Backed Loans to Fuel Growth

In a decade-long scheme, the meat processor bribed more than 1,800 Brazilian politicians to secure Brazilian government development loans, which JBS admitted helped it take over the U.S. beef market. With these funds, JBS was able to acquire more than 40 rivals on four continents between 2007 and 2017.

JBS’ Owners Defrauded Four Brazilian Pension Funds Out of $2.5 Billion

The Batista family of Brazil owns JBS and several other Brazilian companies. The Batista brothers, Josely and Wesley, led a stock fraud scheme that defrauded four Brazilan pension funds out of $2.5 billion.

JBS Was Caught Bribing Meat Inspectors

In 2017, JBS was caught exporting rotten meat worldwide and trying to cover up the stench using cancer-causing acid products.

JBS Ripped off U.S. Cattle Farmers and Ranchers

In 2018, USDA found JBS had ripped off U.S. cattle producers at three separate slaughter facilities by shorting them on payments for their cattle. While the JBS abuses were extensive, USDA settled the claims for a mere $50,000 penalty.

Today, after thirty years of the big meatpackers manipulating the market and managing cattle prices at levels that producers could be conditioned to accept, over 40% of our ranchers are now out of business, replaced with cheap and dangerous imports. Two of our nation’s big-four meatpackers are Brazilian owned. The drastic price drop after the Tyson fire and another even worse crash after the Coronavirus, has finally awakened cattle producers, but so far, USDA continues to do nothing.

Unfortunately, we didn’t listen to the warning from 1990:

Meat Market Slaughter: Competition in meatpacking is dwindling as three big companies gain market share and power. Smaller competitors and state regulators are alarmed.

April 22, 1990

12 AM

TIMES STAFF WRITER

By the end of the week, it was hard to deny that something was wrong in the meatpacking industry:

Monday, March 5: Specialty meat processor Doskocil Cos. of Hutchinson, Kan., filed for protection under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. its major competitors–the so-called Big Three meatpackers–are all angling to snap up the company’s slaughtering facilities, a Doskocil spokesman said.

Thursday, March 8: Farmstead Foods of Albert Lea, Minn., announced the immediate closure and liquidation of plants in Albert Lea and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, throwing nearly 3,000 workers out of their jobs.

Friday, March 9: Oscar Mayer Foods Corp. announced that it would close its Vernon processing plant by the end of September, laying off nearly 550 employees, most of them older workers who had labored at the plant for more than a decade and who hadn’t had a pay raise since 1980.

The three companies reflect sweeping changes in the meatpacking industry–technological advances that make older plants obsolete, increased competition from meats such as chicken and consolidation of the industry–that make it increasingly difficult for smaller firms to compete with the Big Three meatpackers.

“The change in concentration in the beef-packing industries is just beyond any historical precedent,” said John M. Connor, professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University. “I think it’s just a matter of time before the Big Three beef packers learn to cooperate (with each other) rather than compete in the aggressive way they have been in the last three years.”

It’s also just a matter of time before pork processing becomes as concentrated as beef, according to agricultural economists and industry analysts. The watershed year for concentration in the beef industry was 1987; the 1990s could be that threshold time for pork.

Concentration–when a small number of companies control a large share of an industry–is far from merely an abstract concern. It affects workers, farmers, consumers, contends John Helmuth, assistant director of the Center for Agriculture and Rural Affairs at Iowa Sate University.

Because of concentration, “not only have meat prices gone up for consumers, but at the same time prices paid to (farmers) have gone down,” Helmuth said. “Wage rates have gone down. I think that what we’re seeing is that . . . (the big) meatpacking plants are able to keep more of their own profits.”

Concentration

The Big Three meatpackers–IBP Inc. of Dakota City, Neb., ConAgra Inc. of Omaha, Neb., and Excel Corp. of Wichita, Kan.–dispute such arguments, saying that concentration brings greater efficiency, higher prices to livestock suppliers and lower costs to consumers.

“Concentration is not unique to the meat industry,” said Gary Mickelson, spokesman for IBP. “Others have experienced similar changes. . . . The meat industry is responding to a changing market reality and increasing competition from other protein sources. It’s an extremely competitive industry. The companies that were paying the high wages are not there anymore.”

Today, the Big Three beef-packing firms have about 70% market share, and the top four pork-packing plants currently control about 40% of the pork we eat.

By May, the market share for the largest pork packers will increase again, as IBP opens a new pork-packing plant in Waterloo, Iowa, a facility that will be able to slaughter 15,000 hogs each day.

And as concentration intensifies, legislatures and advocacy groups around the country are gearing up to do battle with the Big Three:

* The attorneys general from five Midwestern states have asked the Justice Department to launch an antitrust investigation into the Big Three’s business practices. In an April 12 letter, the attorneys general from North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota and Montana said “there is growing concern over the continued competitive viability of this industry and the enhanced prospect of collusive anti-competitive activities taking place.”

* A handful of state governments are looking into legislation that will do what they contend federal laws have failed to accomplish–bring competition back to the meatpacking industry.

* The National Cattlemen’s Assn. appointed a task force in late 1988 to conduct a year-long study of concentration in the beef industry. The study was published in October. Its top recommendation was that “no more mergers or acquisitions of beef slaughter facilities by the Big Three packers be allowed.”

* The Center for Rural Affairs, an agricultural think tank in Walthill, Neb., will unveil a set of proposals at the end of April recommending such controversial actions as a federal cap to keep any single company from controlling too much of the meat market. That cap would be significantly lower than the market share already controlled by any of the Big Three companies, said Marty Strange, the center’s program director.

* Since the end of January, conferences addressing consolidation have been held throughout the country by interested industry groups. While the organizations vary greatly along the political spectrum, their messages are similar: Stop the Big Three now.

Call for Regulation

Actually, the message might have been “Stop the Big Three–again.” This isn’t the first time that there has been a call for meatpacking regulation. Agricultural economists love to point out that 1990 is the 100th anniversary of the Sherman Antitrust Act, which was created in part to break up the so-called Beef Trust, or Big Four. The act was not particularly effective.

So when the Federal Trade Commission was established in 1914, one of its earliest actions was an investigation of the five largest meatpacking companies. The investigation’s result was a 1920 consent decree in which the “trust,” now the Big Five, agreed to forgo further consolidation and to sell stockyards, railroad equipment, refrigerated warehouses and meat stores.

Just for comparison’s sake, in the 1880s, the Big Four controlled 85% of the beef market. In the 1920s the Big Five controlled 71% of the beef market. Now that the Big Three control 70%, nothing’s being done about it, critics contend.

“Where have our antitrust laws been these past 10 years?” Helmuth wonders. “There have been zero Sherman Act violations brought by the Justice Department since 1980.”

When you’re talking market share in beef and pork, IBP is the indisputable king. It incorporated in 1960 as Iowa Beef Packers and now controls 32% of the national beef market and 15% of the pork market. IBP is a public company whose majority shareholder is Occidental Petroleum, which owns 50.5% of the stock.

Although ConAgra has been in the red meat business since the early 1980s, it occupies the No. 2 spot with 21% of the beef market and 9% of the pork market.

In its 1989 annual report, the company describes itself as the only major U.S. food company operating across the food chain:

“We have major businesses in crop protection chemicals, animal feed, fertilizer, specialty retailing, . . . grain processing, beef, pork, lamb, chicken, turkey, seafood, processed meats, dairy products, potatoes and a broad array of consumer frozen foods.”

Its acquisitions throughout the 1980s exemplify the decade–one of the most volatile periods in the meatpacking industry. The operates 17 plants under a half dozen banners.

Size Advantage

Companies such as ConAgra say size is the only thing that saves them–enormous, efficient, one-story plants and lots of them, technologically up-to-date plants where animals can flow in one end alive and out the other as product.

“You have to have the economies of size, operate the plants on double shifts, get as many head through there per day as possible to be competitive,” said Gene Meakins, vice president of public relations for ConAgra Red Meats Cos. in Greeley, Colo. “You’re dealing–even in good times–on very narrow margins.”

Not everyone buys that argument, though. G. Edward Shuh is dean of the Hubert Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs and headed up a group of agricultural economists that produced a study called “Competitive Issues in the Beef Sector: Can Beef Compete in the 1990s?”

A major point in the study, Shuh said, is that, while some consolidation does save money, the Big Three have eclipsed any economy of scale by getting too big. If the top four meatpackers operated enough big plants to exhaust all economies of scale, the study said, concentration would only range from 24% to 48% instead of 70%.

The major meatpackers consider concentration a natural byproduct of intense competition in a difficult industry. Its critics, however, point to the high costs that concentration has incurred: As the big have gotten bigger, the small have gone out of business.

Between 1972 and 1987, the most recent year for which statistics are available, more than 400 slaughtering packers shut down and some 40,000 jobs were lost. The concentration in beef-packing alone tripled between 1977 and 1987, an occurrence that is “simply outside the realm of experience,” according to the Humphrey Institute study.

Litvak Meat Co. opened its doors in Denver more than 50 years ago, slaughtering about 150 calves daily and employing a half-dozen workers. At its peak, in the mid-1980s, the slaughterhouse processed 1,200 head of cattle each day and had 200 employees.

At one point, Litvak’s Denver neighborhood supported at least 15 similar enterprises within a radius of two miles. Today they’re all gone, including Litvak Meat, which shut down in 1988, a casualty of concentration.

“We weren’t able to buy the live cattle due to the fact that these Big Boys, ConAgra and Cargill (which owns Excel) needed more numbers and outbid us,” said Leonard Litvak, chairman and chief executive of the defunct company. “The FTC allowed it. I don’t think the FTC could stop it. I even wrote the Justice Department; I never heard back.”

Casualties of War

Then there are the farmers, particularly those who operate feedlots and fatten cattle for slaughter. After studying beef prices for a decade, Bruce Marion found that purchase prices paid to farmers were between 0.5% and 1% lower in areas of greatest concentration than they were in areas where many packinghouses operated.

“If you start looking at it from the standpoint of how much do cattle feeders lose in a year that they would have gotten if they had more competitive markets, you’re talking about $50 million a year,” said Marion, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Workers at meatpacking plants have also lost out through concentration and the closure of plants, according to economists and union representatives. In the 1950s, the meatpacking industry instituted cost of living increases for hourly workers, said Patrick Luby, a vice president and economist at Oscar Mayer Foods Corp.

“During the early 1980s, lower-paying companies were expanding,” Luby said. “They had no cost of living agreements. They drove out the old-line pork packers. Many of the plants were sold to new ownership, closed and reopened with lower pay scales. The labor costs did come down or level off.”

The same was true for beef, according to Lewie Anderson, a United Food & Commercial Workers Union vice president. And the union did little to stop it, Anderson said. In fact, industry watchers agree that the union’s strength has greatly diminished.

“The Big Three have not only slashed worker wages, but they have kept the wages of workers depressed for a protracted period of time,” Anderson said in “Return to the Jungle,” a position paper written last year. And concentration has affected wages throughout the industry.

Henry Lopez, a meatpacker at Oscar Mayer’s Vernon plant, hasn’t gotten a raise in the past 10 years. An hourly wage of $10.69 sounded good in 1980, but living at that level for a decade makes it tough to afford such things as health care and college tuition for his two daughters.

Early this month he got the news that the UFCW and Oscar Mayer had negotiated a 25-cent hourly raise, but that did little to improve Lopez’s spirits or those of his more than 500 colleagues. Because by the end of September, the Oscar Mayer plant will close.

“Here’s this company I gave 20 years of my best labor to, and they’re throwing us out the door,” Lopez said. “I don’t understand why I have to leave. I know I’ve given them my best.”

While wages have been depressed because of concentration, Oscar Mayer officials said their plant will close “because the cost of doing business at that plant has steadily increased,” said James Aehl, corporate spokesman. “It has become increasingly difficult to remain competitive in an increasingly competitive industry.”

The Vernon plant was built before World War II and has been renovated several times since, Aehl said. But it’s still a relatively small five-story facility in an era when “new breed” plants are bigger and only one story tall. Multistory plants lose efficiency because meat must be moved from floor to floor instead of flowing through from processing to warehousing.

“You have machinery in plants being technologically bypassed,” Aehl said. “A little bit of this is consumer change in eating more poultry products. We have not closed a large poultry plant.”

Nicholas Spaeth, North Dakota’s attorney general, said antitrust concerns in the meatpacking industry have grown sufficiently in the Midwest that the Justice Department should step in to investigate.

North Dakota, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota and Montana together “considered trying to launch an investigation on our own, but the meatpacking industry is a national industry,” Spaeth said. “We don’t have the resources. The states involved are relatively small and rural.”

The Justice Department has received the letter, but no investigation is planned to date, said Joseph Krovisky, a department spokesman.

“Justice is aware of the concern expressed by meat-producing groups about concentration in the industry,” Krovisky said. “It has carefully monitored the industry in the past and will continue to do so. We do not have any action pending against any of the meatpackers.”

Which basically leaves any action up to the states themselves. Groups such as the National Cattlemen’s Assn. are calling for an end to concentration, but not a breakup of the largest packers. And the National Farmers Union is working with several states to get legislation passed that will do that.

In Kansas, legislation has been introduced to prohibit large packing plants and grain companies from owning and operating feedlots, said Bruce Larkin, a Democrat who represents the state’s 62nd District. “I’d like to see the individuality stay in the operations and maintain more competition.”

The legislation’s intent: antitrust. Its future: questionable.

“It hasn’t been killed,” he said. “But for all practical purposes, it is not going anywhere this year.”

CONCENTRATION IN THE MEATPACKING INDUSTRY

1988: 69.7%

Source, Department of Agriculture

PLANT CLOSURES: IOWA AND NEBRASKA

Between 1969 and 1989, the following beef plants were closed in the states of Iowa and Nebraska, displacing an estimated 7,000 workers.

NEBRASKA

1 Omaha, Nebraska Armour B.C. Dressed Beef Wilson American Beef Palmayer Beef

2 Scottsbluff Swift

3 Grand Island, Nebraska Swift

4 Lincoln American Stores

IOWA

1 Des Moines, Iowa Swift Wilson

2 Estherville Morrell

3 Oakland Spencer Foods

4 Spencer Spencer Beef

5 Council Bluffs American Beef

6 Sioux City Needham Pack Raskin Pack Meyer Pack Mid-States

7 Fort Dodge IBP

8 Postville Hygrade

9 Denison Dubuque

Source: United Food and Commercial Workers Union

Maria L. La Ganga is a Metro reporter for the Los Angeles Times. She has covered six presidential elections and served as bureau chief in San Francisco and Seattle.

2011 – Cattlemen struggle against giant meatpackers and economic squeezes

2012 – Obama’s Game of Chicken