The following article originally appeared on TradeReform.org.

The following is a transcript of a YouTube video. It’s well worth listening to!

I’m a graduating senior, and I’m not worried about the economy or jobs.

It’s all much simpler than we’re being told. So let’s put our political differences aside, have some fun and get some answers to what I call “Questions.”

Like: Where does money come from?

When our country was wealthy, it was because we had the most factories and made the most stuff. Seriously. Agriculture and natural resources also contributed; but, by far, the vast wealth of America was created by American manufacturing.

Curiously, a lot of economic activities grab existing wealth, but don’t actually create any new wealth. Banking and finance, for example, do not create wealth. Services–however necessary–do not create wealth.

Let’s say you and I wash each other’s cars and charge each other $10. We’re working and earning income; the government would include our $20 in its official reports; but we’re not actually adding anything to the economy. But what if we take raw steel and rubber and glass and physical labor, and we build those cars from scratch, and then sell them? When we make things, we create wealth. This means more opportunities, more jobs, more of everything–everything–as long as we keep manufacturing.

Next question: America used to be the land of opportunity. What happened?

Big Business spends big money on American politics. Why? Because it buys influence. This worked OK when Big Business was still American: American owners, American factories, American workers. But then “globalization” caught on. Sounds cool: The Global Economy. But have you noticed that, here in America, the rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer, and the middle class is starting to disappear altogether? What “globalization” really means is that American-based multinational corporations are free to search the globe for the cheapest means of production. Then they close their American factories and fire their American workers.

This is tempting for publicly traded multinationals. They can increase their profits, their Wall Street performance, their executive bonuses; and at the same time give their customers lower prices.

And just think: they can accomplish all of this simply by firing American workers and shutting down American production.

Whoa! Isn’t that the same as destroying America’s source of wealth?

Our leaders used to be on our side. Back when England was a serious economic competitor, Abraham Lincoln said: “If we purchase a ton of steel rails from England for twenty dollars, then we have the rails and England the money. But if we buy a ton of steel rails from an American for twenty-five dollars, then America has the rails and the money both.”

Can you imagine any President saying that today? No way. The multinationals that control our politics would never allow it.

And so the big question: What can we do?

A lot, because you and I have the real power. American consumers are 70% of the entire US economy, and we can turn it around any time we choose.

Suppose every American simply reallocated 1 dollar per day, spending 1 dollar less on foreign-made goods, and 1 dollar more on American-made goods. After a year, we’d have 110 billion dollars, which could mean more than 2 million new jobs paying $50,000 per year.

Other factors are involved–costs, profits, US vs. foreign ownership–but the principle stays true, so let’s keep this simple and make our point. Even one dollar per day can make a big difference.

Reallocate ten dollars per person per day–from foreign to American-made goods–and in a year we’d have 1.1 trillion dollars, or potentially more than 20 million new jobs paying $50,000 per year.

Why stop there?

Financial crisis solved. Unemployment solved. Our future: safe, secure, and back in our own hands.

Like I said, it’s much simpler than we’re being told.

Maybe we’ve been listening to the wrong people.

Which reminds me: Corporations manufacturing in foreign countries? Don’t buy their stock. Why invest in them when they don’t invest in you?

Thanks for listening. Google “American-made goods.” And have a great future.

By Mike Callicrate

By Mike Callicrate “Our ground beef comes from

“Our ground beef comes from

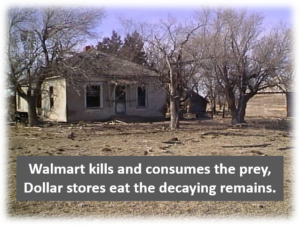

With all their highly touted technology and so-called economies of scale and efficiencies, the industrial food system is collapsing. The predator has consumed the prey. The bones are being picked clean. Slaughter houses, like the Cargill beef plant in Plainview, Texas, are shutting down for lack of livestock. They blame the drought, but abusive market power and monopoly control is the real reason 90 percent of our hog farmers are out of business. Over 40% of our ranchers are gone, and over 85% of our dairy farmers are no longer caring for our milk cows due to a no-rules highly predatory marketplace.

With all their highly touted technology and so-called economies of scale and efficiencies, the industrial food system is collapsing. The predator has consumed the prey. The bones are being picked clean. Slaughter houses, like the Cargill beef plant in Plainview, Texas, are shutting down for lack of livestock. They blame the drought, but abusive market power and monopoly control is the real reason 90 percent of our hog farmers are out of business. Over 40% of our ranchers are gone, and over 85% of our dairy farmers are no longer caring for our milk cows due to a no-rules highly predatory marketplace.