December 3, 2021

The Way to Fix a Flawed Compromise is to De-couple “Negotiated” from “Spot”

By Gilles Stockton

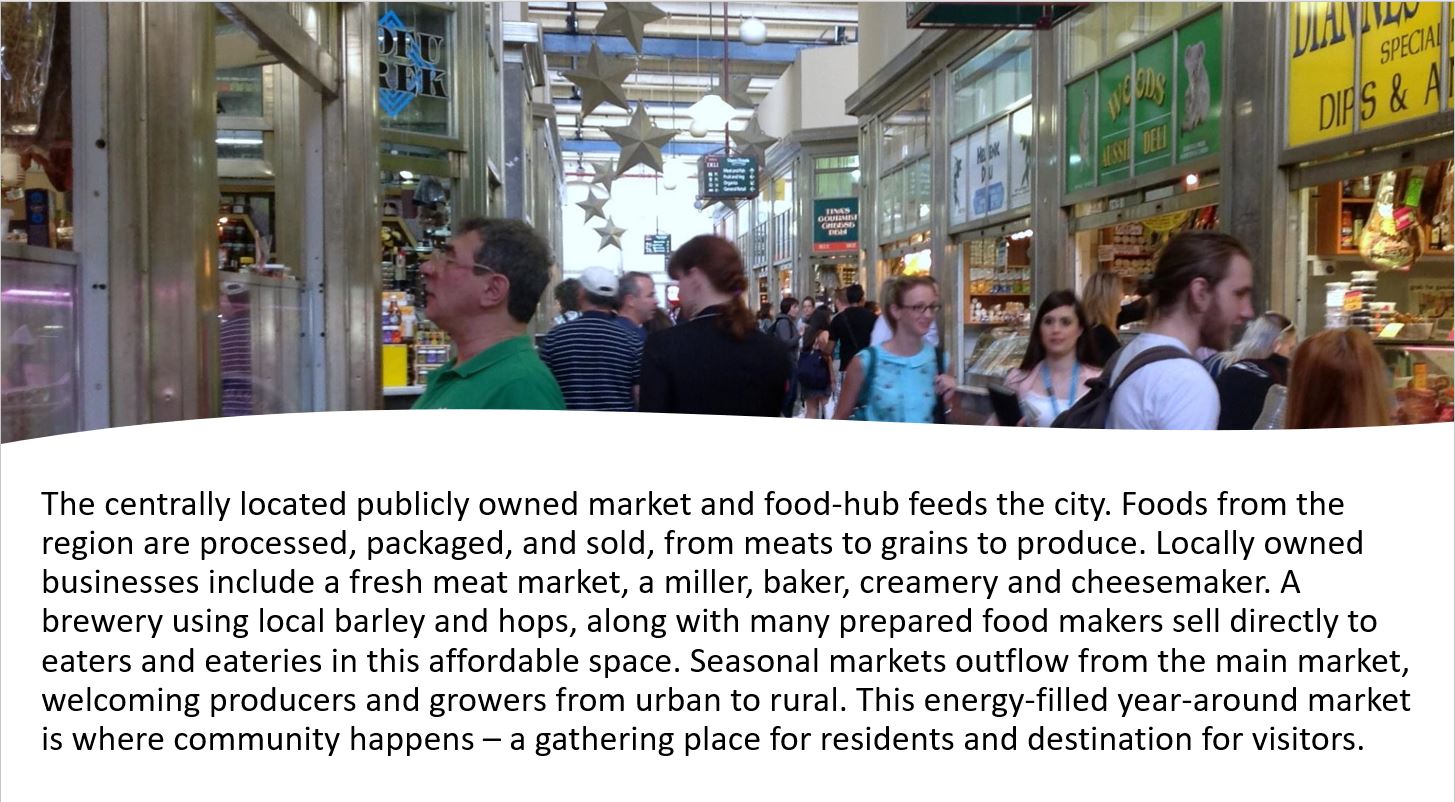

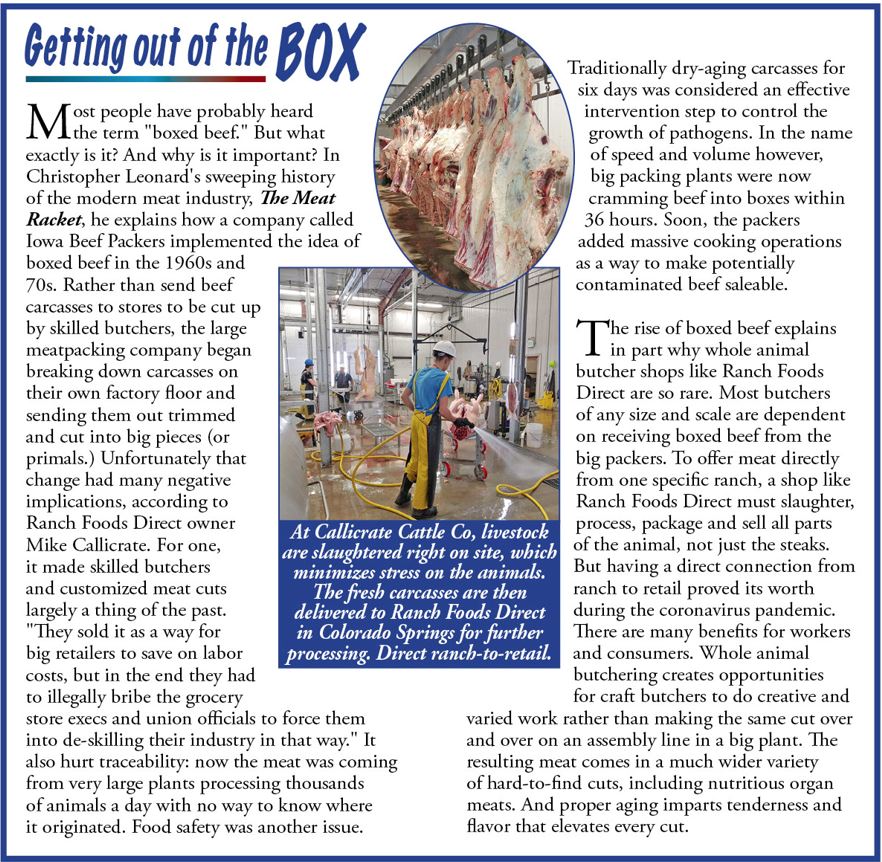

Alternative Marketing Agreement cattle depress the value of better cattle like these Angus/Wagyu cross heifers at Callicrate Cattle Co. Court records from the 2004 Tyson/IBP trial show that the AMA captive cattle were of lower quality and lesser value than the higher quality negotiated cash cattle. The real value of AMA captive cattle is for hammering down the overall price for cattle.

Senate Bill 3229, is said to be a compromise merging the 50/14 concept proposed by Senators Grassely and Tester, with a bill that enhances mandatory price reporting advanced by Senator Fischer. The original version of the 50/14 proposal would require that half of the fed cattle be purchased on the “negotiated spot” market, and Senator Fischer’s contribution would require mandatory price reporting of all fed cattle sales, along with the publishing of a library of forward and formula contracts.

“The real value of AMA captive cattle is for hammering down the overall price for cattle.”

Because less than twenty percent of the fed cattle are sold on the “negotiated spot” market, which is then used to price the remaining eighty percent – this clearly results in inadequate “price discovery.” Absolutely! The number of “spot” market sales must be increased, and fifty percent is a good target. However, the flaw in this proposal is coupling “negotiated” with “spot.” A “spot” market is a “cash” market for immediate delivery. A “negotiated” market is one where the buyer and seller agree in private on the sale terms.

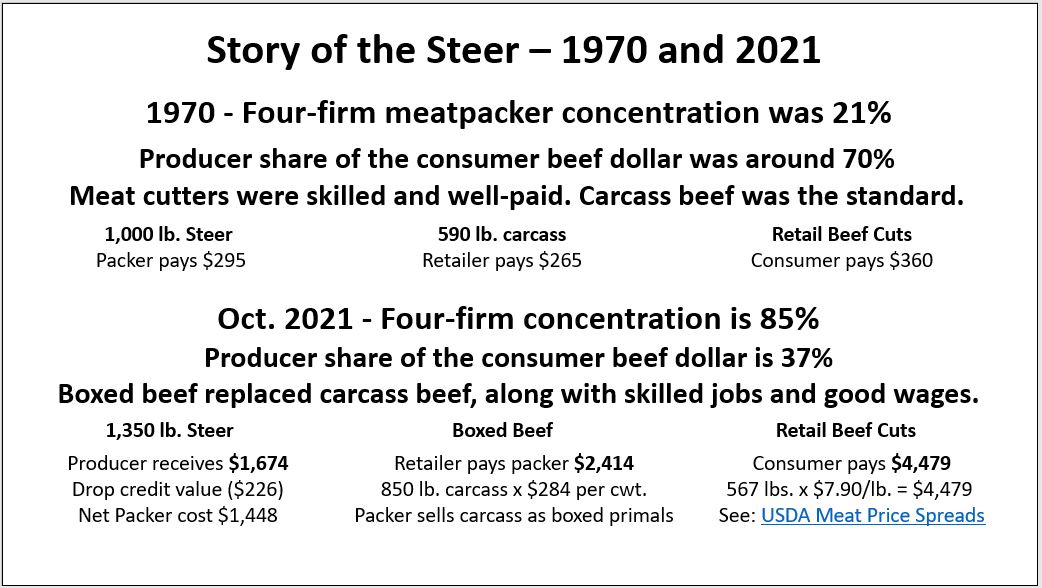

The problem in any “negotiated” market is that there is a built-in bias in favor of the buyer. This is because the seller has already invested their money in the cattle and have much to lose if the market goes down. Buyers, on the other hand, have time on their side and other cattle from which to choose. This dynamic results in a lower “negotiated” price than what “supply and demand” conditions would otherwise warrant.

Economic research confirms this downward bias. If half of the cattle are to be required to be sold on the “negotiated spot” market, this will result in lower overall cattle prices. The solution is to de-couple “negotiated” from “spot” and require instead the use of an electronic/video auction market mechanism for the “spot” marketing of fed cattle.

Here in cow/calf country there tends to be a distrust of auction markets. This is probably because most of us have been burned when a load of calves or culls were sold for less than they should have. Because of these bad experiences many ranchers prefer to market their calves by “negotiating” with a trusted buyer. The feeling is that not only is one avoiding the risk of a bad sale, you are also avoiding the four percent auction fee, and the shrink when your calves wait three or four hours to be weighed after already being on a truck for two.

“The most efficient and most accurate way to arrive at optimum “price discovery” is through an auction.”

There is, therefore, a legitimate reason to prefer to “negotiate” rather than sending the calves to the auction barn. However, an electronic/video market overcomes many of those objections. And too, does one really avoid the four percent marketing fee? The buyer with whom you “negotiate” also has costs that need to be covered. The reason that the “negotiated” market for feeder calves works as well as it does is because a significant number of calves are sold at the auction barns or through the electronic/video auctions. This provides an honest reference. The most efficient and most accurate way to arrive at optimum “price discovery” is through an auction. It may not be perfect, but auctions are, in the long run, better than all of the alternatives. And too, the prices derived at a public auction is open for all to see.

In the fed cattle market, there is no honest reference, because all “spot” market sales are “negotiated.” We mitigate that to some degree by mandatory price reporting. The better solution would be to require that the “spot” market be conducted through an electronic/video auction where not only is “price discovery” more accurate, the market information is public.

“We are told by the beef packers, their captive economists, and the NCBA that it is absolutely essential that most of the cattle be marketed through alternative marketing agreements …”

Why stop there, why not require that all fed cattle be sold in an electronic/video auction. Just as in the case of the electronic/video sales for the future delivery of feeder calves, an electronic/video auction for future delivery of fed cattle would work very efficiently. As with feeder calves, where a base price is set at the time of the sale and adjusted at the time of delivery, appropriate terms can be incorporated in the contract.

We are told by the beef packers, their captive economists, and the NCBA that it is absolutely essential that most of the cattle be marketed through alternative marketing agreements (AMA) – better known as “captive supply.” Otherwise, they contend the quality of the cattle will deteriorate and consumers will stop buying beef. By employing an electronic/video market mechanism, operated by an independent marketing company, packers can enter into forward delivery contracts where the base price would be adjusted at the time of delivery to compensate for actual carcass quality.

“Such a market would preserve all of the alleged benefits of the current “captive supply” system, except that the packers would not be able to manipulate cattle prices …”

Such a market would preserve all of the alleged benefits of the current “captive supply” system, except that the packers would not be able to manipulate cattle prices in their favor. If the “spot” market sales were also reached through an electronic/video auction, the entire market for fed cattle will be open and competitive. Optimum “price discovery” would result.

This in turn would allow the feeder calf market to be more competitive. Instead of the current situation where the continual losses by the feeders are passed down to the cow/calf producers, actual supply and demand conditions would prevail. In 1921 they solved the monopoly problem of their day by requiring that cattle be purchased in an open and competitive forum. It worked then, and it will work now.

Gilles Stockton

President, Montana Cattlemen’s Association

Grass Range, Montana