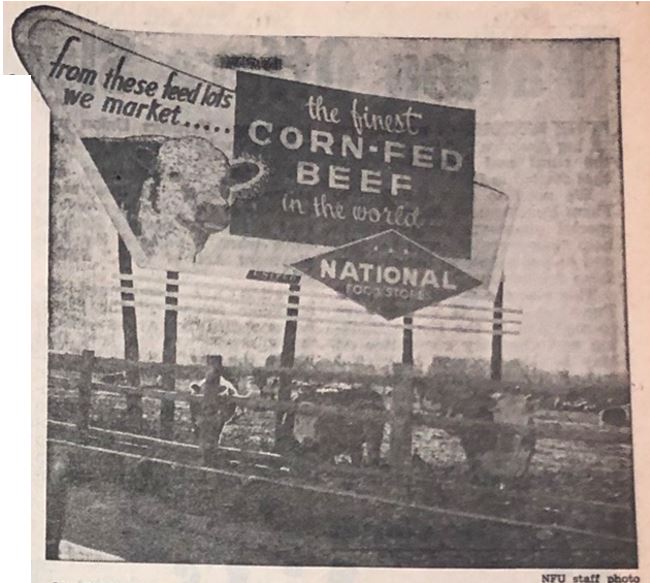

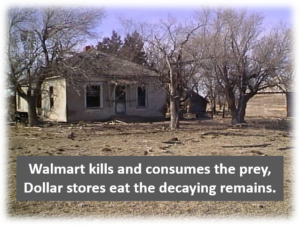

CHAINFEEDING – Typical chain store feeding operation, north of Denver, handles an estimated 20,000 head per year for National Food Stores. Others nearby handle up to 40,000 head per year. Feeders are purchased direct, bypassing marketplace, and go from feedlot to chainstore’s packing plant. This chain slaughters 1,500 head per week for Denver-area market alone.

By Roscoe Fleming

Publication Date: June 1958

U.S. Senate votes to Close FTC-USDA loophole that let chain stores evade trust charges.

The U.S. Senate has voted to wrench the great supermarket chains – which sell one-third of the nation’s food – from the kindly, non-regulating arms of Ezra Benson, and put them under the Federal Trade Commission.

This meant no regulation at all, since USDA has not enforced the packers’ section of the Packer and Stockyards Act of 1920.

For years the chains have managed to escape from FTC regulation by qualifying as “packers,” which put them under the Department of Agriculture. This meant no regulation at all, since USDA has not enforced the packers’ section of the Packer and Stockyards Act of 1920.

One effect if the bill becomes law may be to check the rush toward “vertical integration,” which has hurt livestock producers, since food companies would no longer be able to escape regulation by becoming “packers.”

The senate passed a version of S. 1356 by Senators Watkins (R-Utah) and O’Mahoney (D-Wyo.). The final version was worked out by Senators Carroll (D-Colo.) and Young (R-N.D.). It would be effective for three years. The House still must pass the bill.

Regulation of livestock and poultry marketing would remain with the Department of Agriculture, through the packing houses. Agriculture would actually get wider powers over marketing of all livestock in interstate commerce. Now it is restricted to regulating the larger “posted” and terminal markets.

But “packers” would be specifically subject to FTC regulation of their unfair business practices – which is what they have escaped by fleeing to the arms of Agriculture.

The House still must pass the bill, and Farm Bureau and other forces that oppose it are expected to weaken it there. Some farm observers feel that it is too weak already.

USDA’s failure to enforce the packer section of the Packers and Stockyards Act has had two effects:

- The huge supermarket chains, when charged by the FTC with unfair or monopolistic practices, have successfully slipped out of FTC control by claiming they were “packers.” (See accompanying list.)

- Both to qualify as packers and because it is cheaper and thus increases meat-handling profits, many have gone to “vertical integration” in the livestock country, buying lean animals at the farm or ranch, fattening them in their own huge feedlots, and slaughtering them in their own plants.

HIGHER PROFITS AT BOTH ENDS

This in turn enabled them to make higher profits from meat than those retailers who bought from the traditional packers, who in turn bought from the traditional “stockyards” or terminal markets.

The result was to depress livestock prices clear back to the farm or ranch, according to Senators Watkins, O’Mahoney, Carroll and Young.

But housewives got no benefit. Meat prices at the city counter are nearly at an all-time high, housewives are blaming the livestock growers …

But housewives got no benefit. Meat prices at the city counter are nearly at an all-time high, housewives are blaming the livestock growers– and the Department of Agriculture is bragging of higher farm prices based mostly on this peaking of meat prices.

The massive change in marketing practices is shown by a recent Department of Agriculture report that– even in 1955– more than half of all “animal units” sold for slaughter in the U.S. were bought elsewhere than at the terminal markets.

This tendency has since steepened fast. In 1953, 96.8 percent of all cattle bought for slaughter in the Denver area, for example, were bought through the Denver Union Stockyards, a typical terminal market. By 1957, this figure had slid to 74.8 percent. The terminals have become desperate at so much loss of business and tried to check it.

Denver Union Stockyards Co., for example, made a rule in 1955 that, within about nine-tenths of the area of Colorado, traders had to bring all their livestock to it for market, or be shut out of using its facilities altogether.

YARDS GET SLAPPED

This oppressive rule was approved by the Department of Agriculture. When a farmers’ cooperative fought it all the way to the Supreme Court, Department of Agriculture lawyers defended it. In a ringing decision written by Justice W. O. Douglas, the Supreme Court recently knocked it out, declaring:

“…The (company’s) argument is promised on the theory that stockyard owners, like feudal barons of old, can divide up the country, set the bounds of their domain, establish ‘no trespassing’ signs, and make market agencies registering with them, their exclusive agents.”

The stockyards have tried other expedients. For example, they are supposed to be auction markets, but, at some of them, buyers sought to get around making the purchase an actual auction by using the “turn system.”

Only one buyer would make an offer at a time – and, if this were rejected, the owner of the livestock would be left to stew, with stockyard expenses running up …

Only one buyer would make an offer at a time – and, if this were rejected, the owner of the livestock would be left to stew, with stockyard expenses running up, until the next day when maybe someone else would bid. This practice has supposedly been abandoned also.

DIRECT BUYING KILLS MARKET

But the many of the nation’s 66 “terminal markets” have become virtually sideshows. Particularly in the West, the bigger business is now back at the feedlots. Whether independently or retailer-owned, many feedlots each fatten thousands of animals yearly, doing an annual business that runs in to the millions of dollars. They buy direct from the range and sell for slaughter– and usually directly to the packer.

In turn, some of the largest packing houses outside the “big four,” are now run by retail chains. Two such in Colorado each year slaughter, respectively, about 100,000 and 75,000 cattle. In other words, the era of “big business” has now fully come to the livestock industry, with resulting massive effects all up and down the line—most of them depressing for the actual livestock farmers in the back country.

One odd angle is that the packers, who “consented” back in the early 20’s to stay out of retailing – under threat of anti-trust prosecution—now find themselves facing stiff competition right in their own backyards from the big food chains.

So, they are pleading with the Department of Justice for escape from the consent decree. If they get it, we may see Swift and Armour retail markets blossoming all over the country.

‘Big 7’ Chains Claim Packer Protection

Among the supermarket claims that have qualified as “packers” and thus under present law escape Federal Trade Commission anti-trust jurisdiction, are:

The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Co., with 4,650 supermarkets and doing $4.5 billion worth of business yearly –or 10 percent of all American retail food sales.

Safeway, doing $2 billion annual business in 2,000 supermarkets.

Kroger, doing $1.5 billion in 1,500 supermarkets.

American Stores, doing $650 million in 1,000 markets.

National Tea, doing $620 million in 760 supermarkets.

First National, doing $500 million in 660 supermarkets.

Food Fair, doing $500 million in 240 supermarkets.

Scores of smaller chains have also qualified as “packers,” and together these “packers” do almost one-third of the nation’s retail food business.

The big food processors, too, have joined the procession. Among those qualifying as “packers” and thus under the benevolent jurisdiction of the Department of Agriculture, are:

Proctor and Gamble, Campbell Soup Co., Carnation Co., Quaker Oats, Seabrook Farms, General Foods Corp., Beatrice Foods, Stokely-Van Camp, and scores more.

Approximately 2,000 companies are registered with the Department of Agriculture as “packers.”

Thanks to NFU Historian, Tom Giessel