April 28, 2020

By Gilles Stockton

The collapse of cattle prices following the outbreak of coronavirus has most certainly got our attention and has sparked an intense desire to do something about it. One idea that has gotten traction is to require that beef packers purchase more of their cattle in the spot market, which at best has been only 20% of the cattle and sometimes nearly none. Both the US Cattlemen’s Association (USCA) and R-Calf have come up with competing versions of this idea. USCA wants 30% of total fat cattle sales to be made in a spot market while R-Calf ups the ante to 50%. My feeling is that we had best beware the law of unintended consequences.

The collapse of cattle prices following the outbreak of coronavirus has most certainly got our attention and has sparked an intense desire to do something about it. One idea that has gotten traction is to require that beef packers purchase more of their cattle in the spot market, which at best has been only 20% of the cattle and sometimes nearly none. Both the US Cattlemen’s Association (USCA) and R-Calf have come up with competing versions of this idea. USCA wants 30% of total fat cattle sales to be made in a spot market while R-Calf ups the ante to 50%. My feeling is that we had best beware the law of unintended consequences.

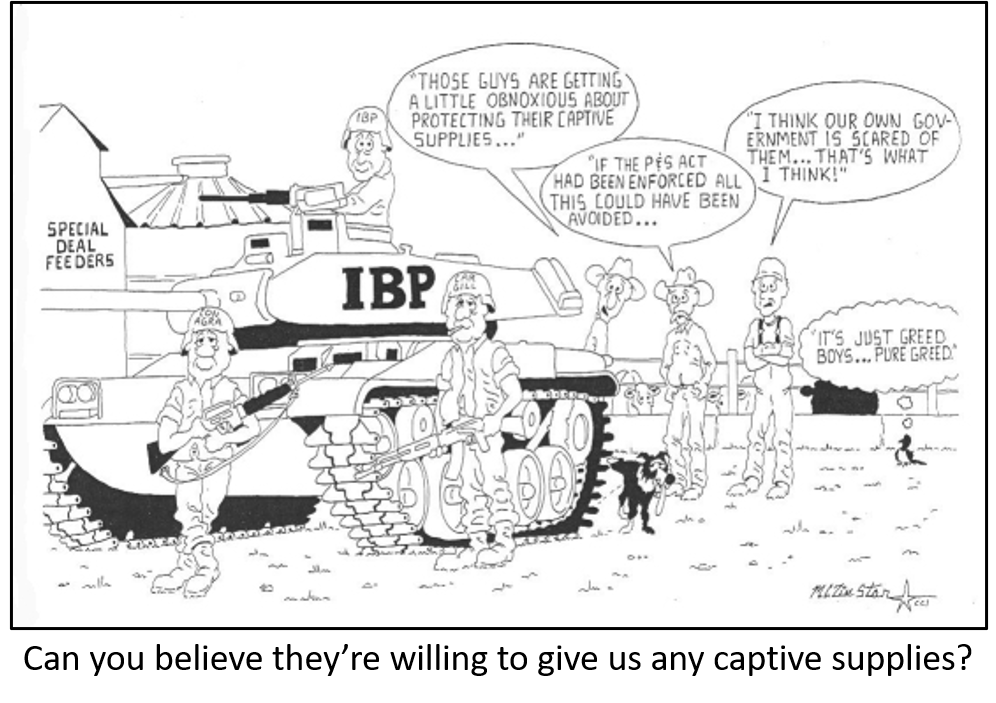

More cattle purchased in the spot market would probably semi-solve a problem in pricing cattle sold under formula and basis arrangements (captive supply). But it is the unintentional flip side that is the problem. Requiring a certain level of spot market purchases sanctions the captive supply practices which make up the rest of the market – 70% captive supply in the case of the USCA’s plan and 50% in that of R-Calf. This would not be good.

In looking to solve one problem, USCA’s and R-Calf’s proposals unintentionally concede that the packer monopoly and market dysfunction is inevitable. Passage will add to the economic forces pushing cattlemen to join the ranks of chicken and pork producers as vertically integrated cogs in a giant meat machine. An actual public competitive market for cattle will be a thing of the past as is already the case for chickens and pigs. I am sure that the proponents of enhanced spot market purchases do not desire this outcome.

Requiring packers to buy more fat cattle on the spot market will not increase competition or price discovery. The spot market is nothing more than a negotiated sale for near term delivery. Because of the Mandatory Price Reporting law, spot market sales must be reported, which at least is a positive thing. The spot market price, in turn, is used to settle the delivery price for the captive supply cattle.

It will still be the same four packers buying and each will still have their own territories, which effectively eliminates any chance for competition between them. And there would still be no opportunity for a small competitor to bid against the big boys. In short, requiring that packers buy more cattle for immediate delivery would shine a little light on cattle pricing practices, but not nearly enough.

The worst effect of this approach is that it would undermine the most important protection we have that is written into the Packers and Stockyards Act – the prohibition of undue preference or unreasonable prejudice:

It shall be unlawful with respect to livestock . . . for any packer . . . to:

- Engage in or use any unfair, unjustly discriminatory, or deceptive practice or device; or

- Make or give any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular person or locality in any respect whatsoever, or subject any particular person or locality to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever; or . . .

The way that the market for fat cattle has evolved is plainly in violation of the P&S Act because it is based on secret arrangements that are predicated on undue preference and unreasonable prejudice. The reason that this happened is that beginning about 1980, the Justice Department made a policy decision to stop enforcing the antitrust laws.

Neo-Liberal economic theory coming out to the Chicago School of Economics became the government’s de-facto anti-trust policy. Under this economic theory, it is assumed that larger firms have natural economies of scale which in turn results in lower prices for consumers. The effect on the market for those of us who supply the dominant firms with raw materials is, under Neo-Liberal economic theory, irrelevant.

But the anti-trust laws are still on the books, and the Packing Cartel would no doubt be delighted if the Packers and Stockyards Act was weakened. All that I am writing here would be merely academic if there were no proposal out there that would actually fix the cattle market dysfunction – once and for all. Not only has one been proposed, but it has also been vetted from both a legal and economic perspective. In addition, in 1999, USDA actually held a hearing on this proposal with nationally recognized legal and economic experts debating the pros and cons.

Of all of the ideas that have been tossed around, only Captive Supply Reform actually solves our problem. It simply states that in order to be compliant with the P&S Act, 100% of the fat cattle must be purchased through a public market. This can be an exchange where the price and terms are publicly offered, or preferably a virtual auction, similar to the video market through which a large number of forward contracts for feeder calves are sold.

The actual wording is very simple. Captive Supply Reform only requires that a base price be set at the time the contract is agreed to. Instead of mandating that a set percentage of cattle be purchased on the spot market, feeders and packers would be free to enter into forward contracts for any length of time that is convenient for their purposes. Just as in feeder calf forward contracts, a base price would be set along with a list of conditions that will adjust the final settlement.

If packers desire to also be in the cattle feeding business, their cattle would have to be offered for sale in a public forum. If fat cattle are shipped in from Canada, these too would have to be priced through a public forum. The beauty of all this is that no regulatory agency would be needed to monitor the program because all of the prices and terms of sale would be publicly open. The other beauty of Captive Supply Reform is that, although it does not break up the packer cartel, it would allow, for the first time in half a century, true competition by start-up specialty packer firms.

I have been told that Captive Supply Reform is too ambitious and that it would be better to tinker by fixing the cattle market in incremental steps. Besides, I have been informed, there is currently interest in Congress to require more cattle to be sold on the spot market and we should take advantage of this interest. But have the allies in Congress actually held hearings and debated the pros and cons – and the alternatives? I don’t think that this has happened.

This coronavirus pandemic has revealed how vulnerable our globalized economy actually is. Outsourcing of manufacturing, just in time delivery, dependency upon autocratic governments, control of important industries by criminal elements, the wholesale monopolization of key industries – Free Trade is revealed as a cynical lie. In agriculture, beef markets are undermined by imports while wheat, corn, and soybean exports are vulnerable to every global hiccup.

It is clearly time to rethink the structure of our economy including a complete overhaul of farm and rural policy. Captive Supply Reform was proposed by a number of western state’s senators back in 2007, but it was our organizations that failed to coalesce to push for its passage. Division, among like the minded cattle producer organizations, has failed us time and again. However, we now see how vulnerable our future as independent cattle producers has become, the time has come to unite and restore competition to the cattle market.

Gilles Stockton

Grass Range, Mt 59032