Farming is one of the fine arts. “The material out of which art is made is everywhere; but the artist appears only at intervals.” The idea is prevalent among farmers that life must be a grind, a dull monotonous routine, devoid of beauty or enjoyment to all but the fortunate few. As soon as we realize that what we call life is opposite of this idea, the sooner will our farmers become artists. The farmer’s work and life was not intended to be devoid of beauty. One’s surroundings may be the humblest sort, but we can look beyond these to the beauty of nature and the children’s faces. Is the morning gray and chill in your home? Do the children feel this and act accordingly? Then search for some beautiful objects near you with which to divert your minds.

Why not have in front of your dining room windows a beautiful vine or a clump of bushes. In winter why not fill the windows with blooming plants? By looking out you may see the brown leafless sunflower stalks, that seem to have nothing to recommend them; but watch a minute and there will come a flock of chattering sparrows eager for their breakfast, and it is a cheerful sight to see the stalks bend and sway, while our feathered friends satisfy their hunger by eating the brown seeds just ready to fall to the earth. Call the children to see the birds and observe how quickly the clouds will pass their faces. The farmer’s vocation is rapidly changing its tone, more and more does the farmer feel the sacredness of his calling and more abundantly does he love his life and work.

There is a difference between farming in its sordid sense and farming in its higher sense. First of all we need farming as a fine art as a direct contribution to life; the haphazard business man, the quack doctor and the go-lucky farmer are not good citizens. Thoughtful, earnest men have taken up the task of entering into the struggles of the farmer and the neglect of the farm to see if the incompleteness can not be, measurably at least, done away with. These problems of interest to farmers that are being so ably discussed by the students of these questions with the purpose of accomplishing results, are meeting with a cheering response from farmers; and those who have toiled for many years tell us that immense results have been accomplished in uplifting the general tone of farming, although the pessimistic farmers can see nothing but drudgery.

The Farmers Advocate is doing great work toward making one of the fine arts, and the readers can greatly assist by standing for the highest and best in farming, and all can testify to your faith by your good work.

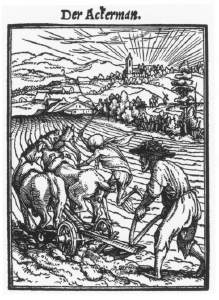

The Plowman from Dance of Death credit: Web Gallery of Art

In connection with prevailing ideas concerning the curse of drudgery, two pictures come vividly to mind—one is “Holbein’s Plowman,” with its barren fields, its poor cabin, worn out horses, and the son ragged cheerless and sad faced. This legend appears under the picture:

“By thy sweat of thy face, Thou shall maintain thy wretched life.”

The very common notion of farm work, its misery and horror is here present. The other picture is that of a bright October morning, when for the first time, a youth went to strike a furrow and to do a man’s work. With the first rod the plow struck a rock and the boy tumbled headlong. By nightfall every muscle and bone ached, and the work did not merit much praise, but the youth’s face was bright with hope and he was happy with the wholesome satisfaction that comes from achieving. There is an essential difference between the plowman and the happy boy; it was not in the kind of work, nor in the reward; the Plowman had his board and clothes; so had the boy; the surroundings of both were the same country life, country skies and country associations; but there is a marked difference. The two workers had been differently educated; the boy had been born and trained to Virgil’s philosophy “Happy the man of the fields if he only knew it.” While the plowman could gain no inspiration, no hope, no love for the work; the boy loved his work and the results of it were pleasures in themselves; it was a beautiful, sensible and satisfactory idea of life.

There had been and still is something wrong with educating our young people to feel and think the lot of the farmer a curse, and thus the young man or woman who remains on the farm must be cuddled and pitied.

The man who molds a beautiful statue of clay is an artist; so is the man who tills the soil in the right spirit. Taking care of cattle is as noble as climbing trees of knowledge, sowing seed if properly understood is on par with preaching a sermon; both have to be done in the right manner and in the right spirit to be among the fine arts.

From the archives of Tom Giessel